Collective concern

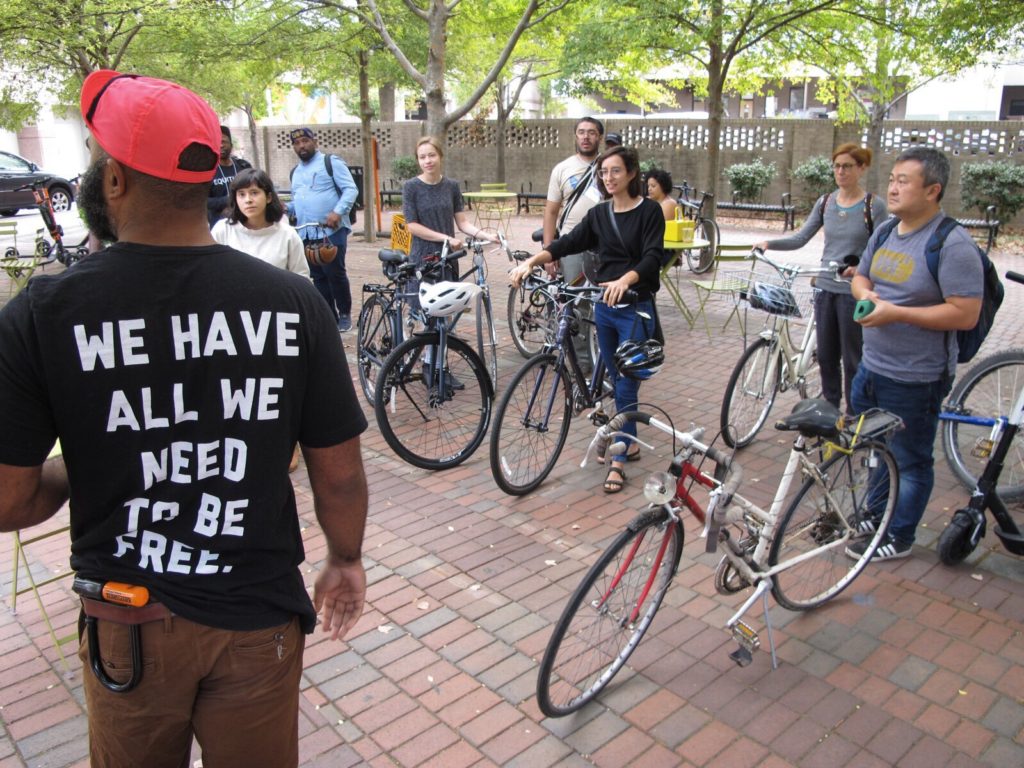

I had a fascinating time at Untokening Durham. I am reflecting on of some of the great sessions and conversations I had, especially with Aidil Ortiz, Aya Shabu, Oboi Reed, Josh Malloy and Bonnie Fan. But my most prominent memory right now is of riding to dinner.