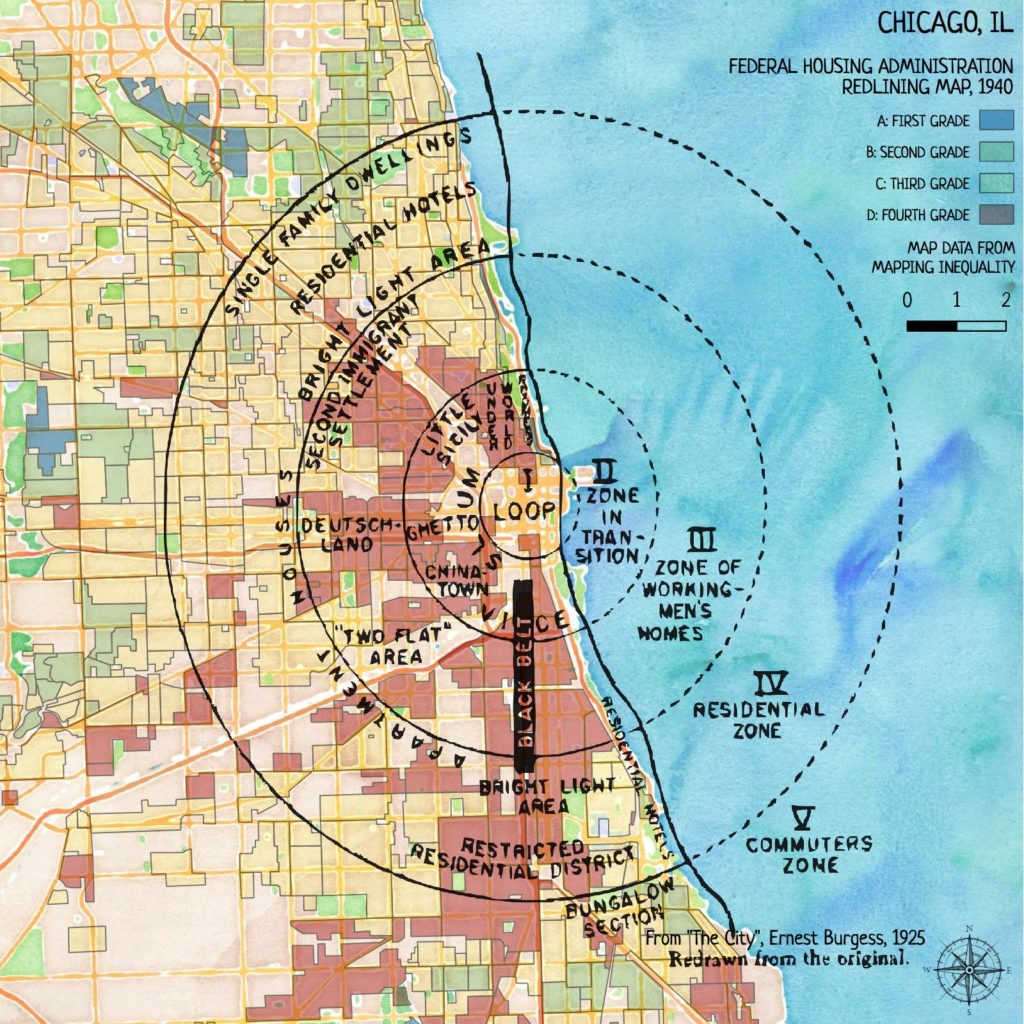

Burgess concentric circle map in GIS

I’m going to be doing some mapping for a project from Equiticity, and one of the themes will be historical spatial inequities in Chicago. This got me thinking about the highly influential concentric-circle city development map drawn by Ernest Burgess (Chicago School of Urban Sociology) in 1925.

Surprisingly I couldn’t find a usable GIS representation of his drawing. So I decided to work on my georectifying skills and put one together.

You can see how Burgess’ racist ideas led directly to racist housing policies.