Letting the community lead

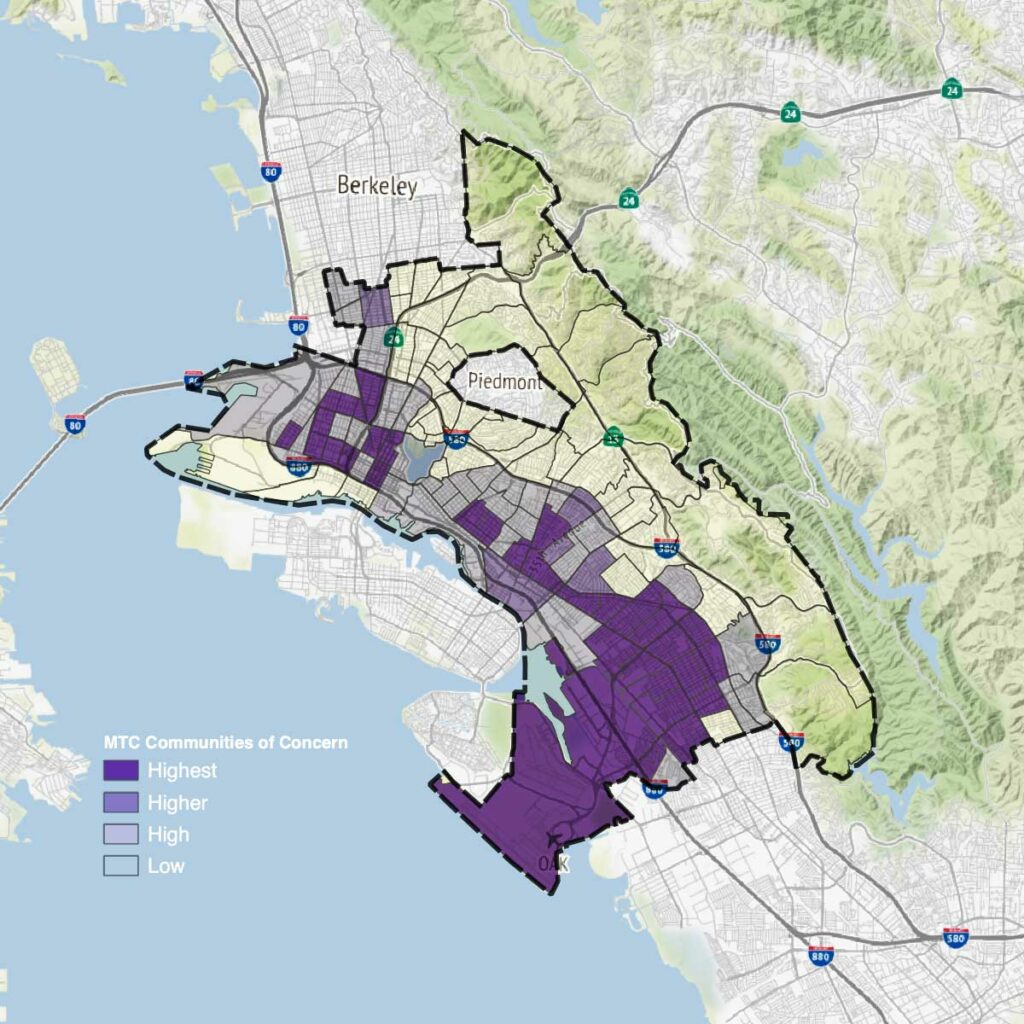

Oakland’s Department of Transportation continues to work towards aligning city practices with the values expressed in its Geographic Equity Toolbox. The latest example is a report on the community engagement for a now-adopted Community-Led Traffic Safety Pilot program, which was received very differently in neighborhoods which have a history of being harmed by infrastructure projects.