A cool side effect of having chosen Minneapolis as one of the study cities is that Saint Paul is right next door. The Twin Cities are small enough that they could be a single city; their combined population is ~700K, smaller than San Francisco’s. (The metro area is ~3.6M). But because of the way they were originally founded, and how they’ve grown over the decades, they have very different administrative structures, infrastructure, and politics.

I met with Reuben Collins from the City of Saint Paul about biking in Saint Paul, and the differences between the two cities. Ruben has some interesting thoughts on bikeway design on velotraffic, and I like his pragmatic approach to bike infrastructure.

I asked him if the ACS mode share data (which show more commute cycling in Minneapolis by an order of three) were really indicative of a difference between the cities, and if so, why would that be? His response was that the difference is real, and that a lot of it is related to long-ago decisions about the built environment. In the 19th century Minneapolis created a powerful parks board, and hired Horace Cleveland, a student of Frederick Law Olmsted, to design a park system similar to Boston’s Emerald Necklace. This resulted in the preservation of land along the river and around the lakes, which today provides Minneapolis with a lot of non-motorized space to work with that Saint Paul simply lacks. There are also two railroads and a freeway cutting breaking up any north-south corridors in Saint Paul, and a significant incline in and out of the city center.

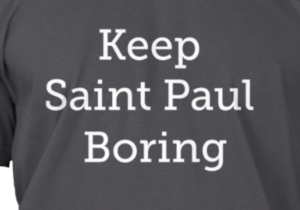

All of that was interesting, but the thing that really caught my attention was Reuben’s mention of the “Keep Saint Paul Boring” campaign. One of the things I noticed in Austin, where people want to Keep Austin Weird, is that the way that Austin is weird is more or less the same as the way Portland is weird. They have the same coffee shops, the same brew pubs, the same beards, and the same city bikes. What started as a counter-culture founded by bike messengers has become commoditized and sold as part of the new urbanity. “Keep Saint Paul Boring” is a bit tongue-in-cheek, but there’s a real way it’s a rejection of hipster culture, and specifically neighborhood change. It represents the tension on one edge of the identity politics of bicycling; people comfortable with post-war, auto-oriented suburbs vs. new urbanists. In the “weird” culture, the bike is a counter-cultural status symbol, a rejection of traditional Americana. Saint Paul is more Garrison Keillor than Sleater-Kinney, and that’s part of why there isn’t as much support for bike facilities and bicycling in the smaller of the Twin Cities.

All of that was interesting, but the thing that really caught my attention was Reuben’s mention of the “Keep Saint Paul Boring” campaign. One of the things I noticed in Austin, where people want to Keep Austin Weird, is that the way that Austin is weird is more or less the same as the way Portland is weird. They have the same coffee shops, the same brew pubs, the same beards, and the same city bikes. What started as a counter-culture founded by bike messengers has become commoditized and sold as part of the new urbanity. “Keep Saint Paul Boring” is a bit tongue-in-cheek, but there’s a real way it’s a rejection of hipster culture, and specifically neighborhood change. It represents the tension on one edge of the identity politics of bicycling; people comfortable with post-war, auto-oriented suburbs vs. new urbanists. In the “weird” culture, the bike is a counter-cultural status symbol, a rejection of traditional Americana. Saint Paul is more Garrison Keillor than Sleater-Kinney, and that’s part of why there isn’t as much support for bike facilities and bicycling in the smaller of the Twin Cities.