I have been really, really trying to avoid getting into the housing debate. Critical analysis of cycling advocacy has become less unpleasant since many of the most entitled loudmouth bullies decided a couple years back that they would become YIMBYs and focus on housing. Cycling discourse is now a slightly less toxic environment, and I don’t want to wade back into that cesspool.

But transportation and housing are inextricably linked, and my investigation of bike infrastructure’s relationship to gentrification is part of the Bike Lab’s work. It came up in this rambling Twitter thread which was triggered by Phil Matier’s terrible SF Chronicle article.

Generally these kinds of discussions are filled with people talking past each other using meaningless, condescending platitudes like “Econ 101!” and “Correlation is not causation!” This particular conversation, though, got to a slightly higher level after I tagged a number of important folks who do work with mobility justice; several of them actually contributed thoughtful commentary to the thread.

One of those, John Stehlin, I knew when he was at Berkeley working on cycling and gentrification on Valencia Street in San Francisco. His thesis work led to two publications, Cycles of Investment (which was important inspiration for my own research), and now, Cyclescapes of the Unequal City (which is on my list but I’ve not yet read). He shows how the bicycle was used as a symbol of a new, affluent urban lifestyle, and how a road diet and other bicycle projects along Valencia Street were marketed to the city based on economic rationale; that property values and economic activity would increase if the street were changed.

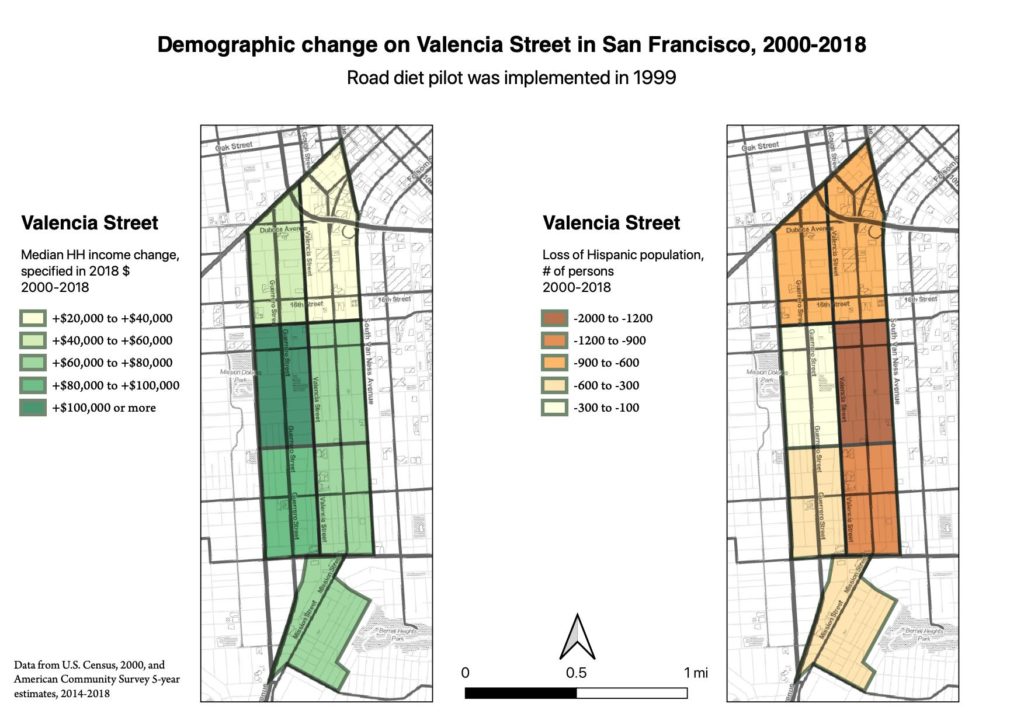

I occasionally reference Valencia Street as ground zero for New Urbanist creative class gentrification. But other than reading Stehlin’s work, and having personal experience of both the Before and After states of Valencia (and all the douchiness in between), I hadn’t actually dove into any analysis on it. The Twitter thread made me dig out my MLK Way code and check out what happened on Valencia between 2000 and 2018. Coincidentally, the road diet pilot on Valencia was implemented in 1999, so my time range happens to coincide with the relevant period of neighborhood change.

The story is mostly what you’d expect; increased income, increased whiteness, displacement of Black and Latino people. But there is another finding which is quite curious, which is that the total population dropped during the timeframe.

Unexpected findings are always the most interesting, so I dug into this one a little more. Since the 2000 Census, these tracts along Valencia Street saw:

- A 34% decrease in Hispanic population (~6,000 persons)

- A 34% decrease in Black population (~600 persons—the neighborhood was only 3.8% Black in 2000)

- A 69% increase in inflation-adjusted median income (from ~$66K to ~$112K in 2018 dollars)

- A 14% increase in housing units (~2,500 units)

- A 4% decrease in population (~1,500 persons)

- A 12% increase in the number of work commuters (~2,500 persons)

Some of these numbers are truly staggering. We built a net of 2,500 housing units in this relatively small area and we actually decreased the residential density. A two-thirds increase in inflation-adjusted median income is enormous. In Census tract 253, west of Valencia between 17th and 22nd, inflation-adjusted median household income tripled. (It’s now $167K).

Even knowing how much the neighborhood has changed, it’s hard to believe how starkly visible that transformation is the census data. And it’s pretty easy to speculate on what’s happening; low-income Hispanic people living in family groups are getting displaced by high-income white and Asian people living alone.

Here’s the thing. These changes weren’t caused by the road diet and bike lanes, but the bike lane project was part of a set of purposeful choices made by the city which changed the spatial regime of the Mission District, and those choices were designed to increase economic output by attracting “creative class” professionals. The transformation is not accidental; it’s explicitly-stated strategy, and the SF Bike Coalition fully engaged with and advocated for the project, using economic development as rationale.

For low-income people who lived through this transformation, of course it feels like colonization. Not only colonization in the sense of the physical occupation of cultural space, but also colonization in the sense of the imposition of a different set of cultural values on that space, with the existing culture largely erased. And of course groups like Calle 24 are suspicious of bike lanes, bike share, and other visible markers of that colonization. They were not included in the vision for Valencia Street’s transformation 20 years ago; if we’re now going to talk about making Valencia Street car-free, will they be included today? Or will they be ridiculed and dismissed as NIMBYs (a term now broadly used to describe anyone who opposes anything that YIMBYs want)?

I would speculate that YIMBYism is driven by the gap between $66K and $112K. Twenty years ago, $80K was a good salary and you could live almost anywhere you wanted to in San Francisco; today, the intensification of income and wealth inequality driven by the current Bay Area tech boom has marginalized not only low-income service and construction workers, but moderate-income college-educated professionals. They’re pissed off about being marginalized, in much the same way as white dudes who took to the streets on bikes got pissed off about being marginalized there. And like those traditional bike advocates, YIMBYs do a poor job of connecting with or caring about the concerns of deeply marginalized groups; their personal experience of disadvantage is all that matters.

One more point. Both YIMBYs and bike advocates claim that we need to make these spatial transformations to combat climate change. In any discussion of housing or bike projects, including the Twitter thread quoted above, someone will attempt to override criticism by urgently stating that “The planet is burning!” But it is very clear that the spatial transformation of Valencia Street has increased per-capita VMT and increased per-capita carbon emissions in this neighborhood. And it has probably also increased per-capita VMT and carbon emissions for the low-income family groups who were displaced from the Mission, who now likely must commute from further away.

White America wants to take up a lot of space, wants to use a lot of resources, wants to be unfettered in its expression of individual choice. If we really want to combat climate change, that’s where we need to start.