I had another follow-up to do while in Washington, DC. During Oakland’s ill-fated plan to sell out its waterfront to John Fisher, OakDOT presented an image from a Washington underpass as a vision for pedestrian access under 880. (My post on that effort: On The Waterfront).

One point I want to make is that utopian urbanist memes, such as those evidenced in the OakDOT presentation, get uncritically shared among urbanists. Whether it’s about Paris, Amsterdam, Tokyo or Hoboken, these visions rarely can withstand scrutiny. Claims are usually inflated, and context ignored.

The presentation which pitched this D.C. installation probably included a picture of some other dingy underpass with a superficial lighting treatment meant to brighten it up—perhaps Oakland’s own Jerry Brown-era project on Broadway (which we’re now trying to revamp).

Activating underpasses is a very difficult thing to do, and it’s dishonest to suggest otherwise. The image used by OakDOT came from a project which had already failed. Let’s try to be forthright about our proposals; otherwise we’ll keep investing in things that don’t work.

Anyway, while I was in D.C. I wanted to visit to learn more about the neighborhood and see what’s going on with the project now.

The neighborhood is what you’d expect from a gentrification project; lots of new generic apartment boxes with underutilized ground-level retail spaces.

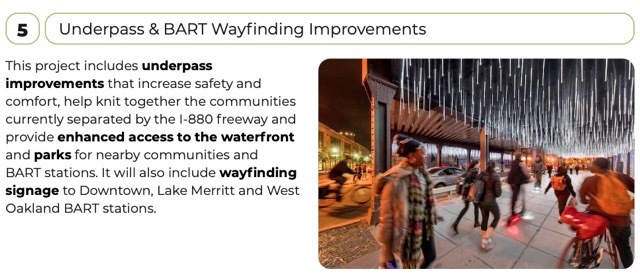

The sparkly lights are still there, and some of the bollards, but now bike infrastructure has moved in. On one side, concrete bollards have been replaced by a Capitol Bikeshare station.

On the other, the bollards have been removed for a bike lane project.

Which leads to the second point I want to make: Bike infrastructure isn’t innocent, and isn’t neutral. [A framing I first heard from Aidil Ortiz at the Untokening conference in Durham, NC.]

The M Street underpass project was never about improving walking safety; it was about clearing out a persistent homeless encampment in order to make the neighborhood more attractive to gentrification. It’s part of a program which has been successful on those terms; median income in the area doubled between 2010 and 2023. Bike infrastructure is bundled into that gentrification package (as noted in John Stehlin’s “Cyclescapes of the Unequal City“). When bike projects are aligned with a larger project to displace lower-income Black and brown residents, it’s a problem, and we need to be honest about that.