Revisiting a bad idea

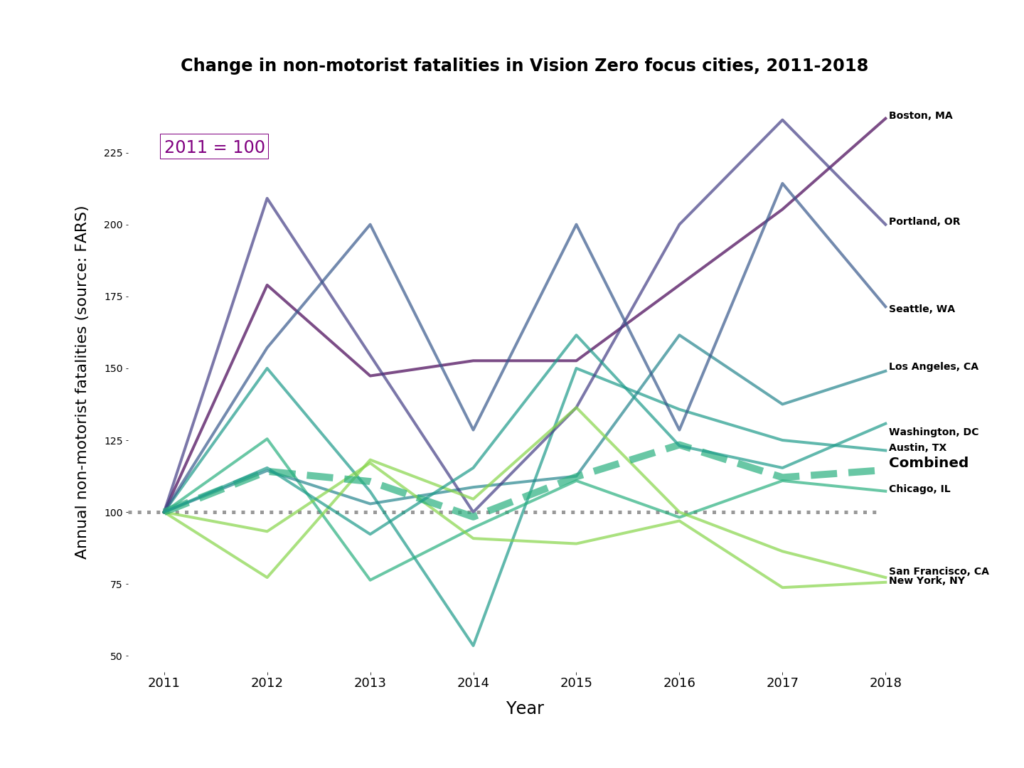

My posts earlier this year suggesting that Vision Zero’s communications strategy of amplifying safety risks might be counter-productive received a little bit of attention. I wanted to revisit the analysis to include the 2018 data from both the ACS and FARS, and to address some methodological criticisms.