As a strategic consultant, I always begin a project by asking my clients what they’re trying to accomplish. Sometimes they already have a strong idea; sometimes I have to help them formulate their thoughts. In either case, during the project we will often refer back to that initial question to inform the choices we make. What are our goals? Are we furthering them?

In streets advocacy, I think we have two core goals: Reducing auto trips, and increasing safety. As advocates we should (I assert) be informed primarily by those goals, and when we consider our tactics, we should consider how they will advance that strategy.

The advocacy response to the recent death of Tess Rothstein in San Francisco raised a concern that’s been troubling me for some time. Our rhetoric around street safety has become increasingly hyperbolic and strident. Crashes are framed as “traffic violence,” using words like “mayhem,” “terrorism,” “slaughter,” and “murder.”

I’m worried that the urgent calls to action we’ve adopted as an advocacy tactic may be undermining our strategy. What if the “Interested but Concerned” cyclists who are always being courted might be scared away by repeated messages about life safety risks?

What if changing the conversation is a bad idea?

I’m not referring to the “don’t read the comment section” morass. I’m speaking about an intentional framing strategy which is integral to the Vision Zero Network’s program. In their communication case studies document, Vision Zero suggests that advocates should, “magnify the threats“, to gain political leverage. The same document lauds VZ New York City’s communications campaign as being, “arresting in its graphic depiction of death and serious injury.” (To be clear: That’s presented as a good thing.)

The strategy aims to create an urgent moral imperative to reduce crashes-not-accidents, using language and tactics appropriated from violence-prevention programs, in order to generate political will for street projects.

The strategy has been successful on one metric: the number of protected lane-miles built. Berkeley built its first protected lanes on Fulton Street shortly after Meg Schwarzman’s near-fatal crash-not-accident there; it since has added protected lanes on Hearst and Bancroft. Tess Rothstein’s death resulted in fast action in lanes on Howard Street, and may accelerate projects elsewhere in the city. [Aside: Another part of the strategy is the repetition of the names of victims.]

But, [putting consultant hat back on] lane-miles is an input metric. We care about output metrics: reduced vehicle trips and increased safety. How are those doing?

Maybe it’s just because I read all the bike stuff, but it seems like these days our emphasis on using crash-not-accident framing to drive policy has resulted in a whole lot of scary and disturbing reporting on the risks of our streets. And I’m worried that this constant amplification of risks could be counterproductive in our effort to convince those “Interested But Concerned” cyclists to get on their bikes.

Data analysis

There appear to be valid reasons for concern. Vision Zero was first developed in San Francisco in 2014, and has since been adopted by cities across the country. In January 2016, the Vision Zero Network selected 10 “Vision Zero Focus Cities“; municipalities with a significant financial and political commitment to Vision Zero concepts.

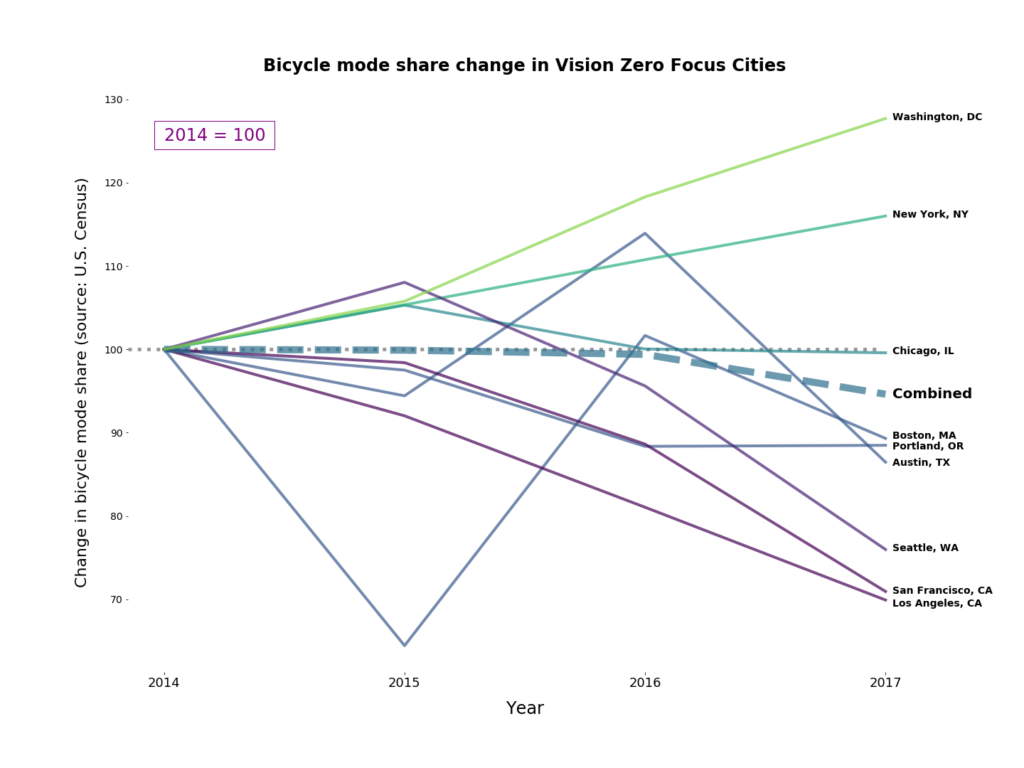

Here’s what’s happened in the nine focus cities with available data. (Fort Lauderdale is omitted because of gaps in ACS data).

Seven out of the nine focus cities have seen declines in bicycle mode share, with San Francisco and Los Angeles seeing drops of nearly 30%. Six out of the nine saw a decline in the absolute number of commuting cyclists. In aggregate, cycling mode share dropped by about 5%. [Aside: ACS mode share data has a number of issues, but there are corroborating data sources, such as the automatic counters on Market Street.]

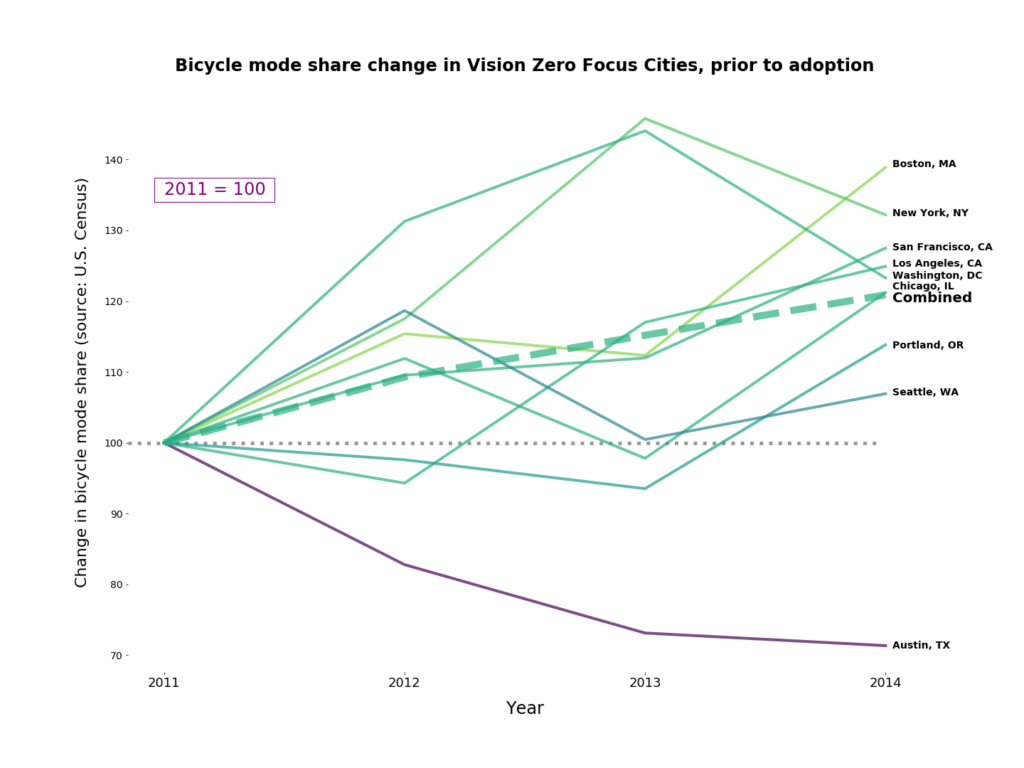

The 2014-2017 drop reversed the trend of the years leading up to 2014, when these cities were gaining cyclists at a rapid pace.

Eight of the nine cities gained cyclists between 2011 and 2014; aggregated cycling mode share rose by over 20% during that period. So, cycling had been growing, went into decline around the time these cities adopted Vision Zero, and went into further decline after they were named Vision Zero Focus Cities in 2016. And the 2018 data, which will include the impact of e-scooters, will look even worse.

Correlation is not causation, but this negative correlation with one of the core output metrics is exactly the opposite of what you’d hope or expect to see from a major advocacy program. That’s concerning.

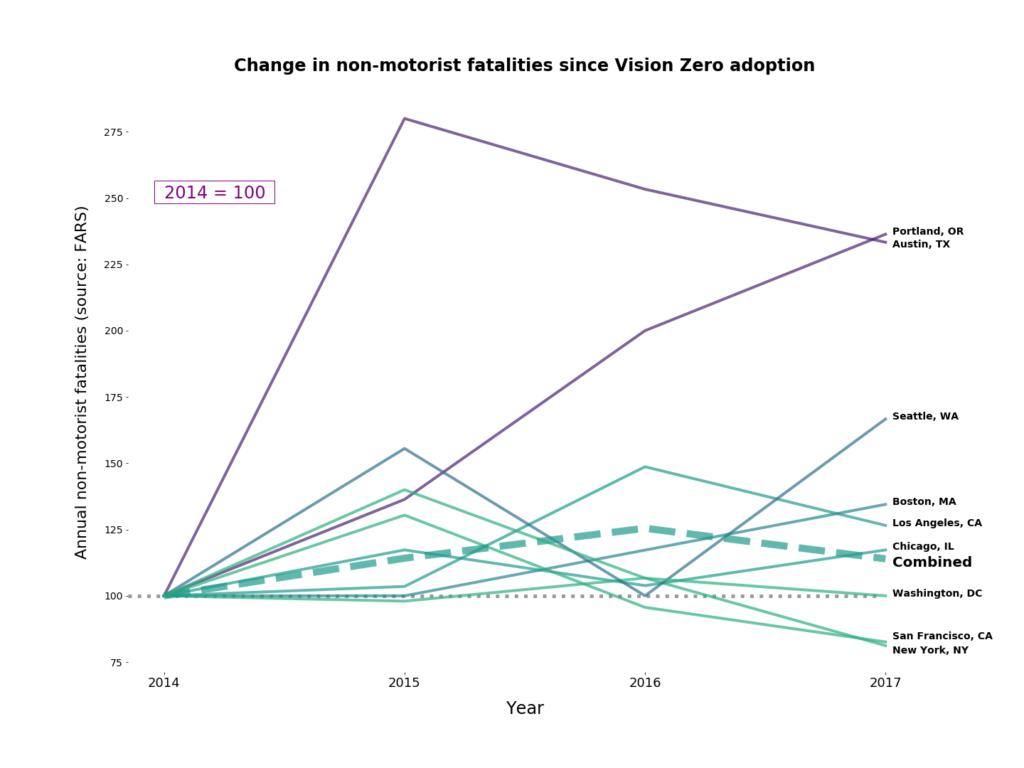

What about our other core goal, increasing safety? Vision Zero’s conception is that we should be able to get to zero non-motorized traffic deaths. Unfortunately, the crash data doesn’t look great, either. Here’s a chart of fatalities among non-motorized road users since 2014:

Fatalities increased in six of the nine cities, more than doubling in Portland and Austin, and decreased in just two. Aggregated, fatalities rose 13% from 2014-2017. Anecdotally, it feels to me like the 2018 data will show an additional increase, but it may be that that feeling stems from the constant bombardment of threat magnification we’ve been subjected to.

Discussion

If this were one of my projects, and the metrics looked this bad four years in, I’d be sounding alarm bells and going back to the drawing board. (Assuming I’d not already been fired). But all indications are that Vision Zero advocates are doubling down on their tactics. Los Angeles is preparing to erect permanent memorials to those killed on the streets, as if that will lead to more people cycling. The rhetoric has reached the point where I’m personally really uncomfortable with it, and I’ve spoken to others in the advocacy world who feel similarly. Are we alienating potential allies as well as potential riders with this moralistic and hyperbolic language?

I’ve written (quoting Lugo) about how combative issue framing could potentially marginalize those from historically oppressed groups. And I do worry about the tone-deafness it requires to use violence-prevention language to elevate bike infrastructure as an urgent moral concern. Chicago from 2014-2017 experienced 24 cyclist deaths, but over 2,400 homicides, with the homicide victims being predominantly poor people of color. Oakland had 7 cyclist deaths and 333 homicides over the same time frame.

But I’m leaving aside that argument for now. I’m making the point that maybe we should abandon the tactic simply because it’s not working.

The New York City “Cycling at a Crossroads” study (2018) begins its crash data analysis with the following statement:

The low number of bicyclist-involved crashes is one of the biggest barriers to conducing safety evaluations of cycling treatments.

Wouldn’t this be a better starting point for a communications plan? “Bicycle crashes are so rare that it’s hard to study them. If you’re concerned about safety, here are some things you can do…”

Urban cycling is similar in risk to other activities (such as driving, hiking, or taking a shower) that we regularly undertake without a second thought. My personal philosophy has long been to model cycling as a normal, everyday activity that anyone can do without special preparation or equipment. That’s why I started organizing rides for geek friends in Berkeley back in 90s, why I built the Bay Area Bike Rides web site, and why I really respect the work of Rich City Rides and the Scraper Bike Team, who do a great job of introducing new cyclists to the roads.

Over the years I have brought many “Interested but Concerned” individuals out on their first real adult bike ride, and many of those went on to become lifelong cyclists. That’s a beautiful thing. I’d like to encourage more of it. And I don’t think threatening them with annihilation is the best strategy.

References

Hammerl, Teresa. “With bike lanes in place, Folsom-Howard Streetscape Project eyes longer-term improvements” Hoodline, 25 January 2019. Retrieved from https://hoodline.com/2019/01/with-bike-lanes-in-place-folsom-howard-streetscape-project-eyes-longer-term-improvements. Accessed on 11 April 2019.

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, National Center for Statistics and Analysis. Available at: http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/ departments/nrd-30/ncsa//fars.html (accessed on 11 April 2019).

New York City DOT, “Cycling at a Crossroads: The Design Future of New York City Intersections”, September 2018. Retrieved from http://www.nyc.gov/html/dot/downloads/pdf/cycling-at-a-crossroads-2018.pdf. Accessed on 11 April 2019

“Project Jupyter.” Project Jupyter, jupyter.org/.

Raguso, Emilie. “Unstoppable: Berkeley Cyclist’s Miraculous Recovery After Crash that nearly Killed Her.” Berkeleyside., last modified Dec 9 2016, accessed Apr 11, 2019, https://www.berkeleyside.com/2016/12/09/unstoppable-berkeley-cyclists-miraculous-recovery-after-crash-that-nearly-killed-her?fbclid=IwAR2_S4n0HRrhPO7XEXiOGuTWXdVrzxjEYaMpjthZ4iPTyTjx-YvgMvmimYQ

Swan, Rachel. 2019. “Cyclist’s Death in SoMa Prompts Outcry, but Action, if any, could Come Slowly.” San Francisco Chronicle, Mar 11, 2019. https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Cyclist-s-death-in-SoMa-prompts-outcry-but-13680493.php.

U.S. Census Bureau (2011-2017) American Community Survey 1-year estimates. Retrieved from https://api.census.gov

Vision Zero Network, Vision Zero Focus Cities. January 2016. Retrieved from https://www.nhtsa.gov/research-data/fatality-analysis-reporting-system-fars. Accessed on 11 April 2019

Vision Zero Network, Communications Strategies to Advance Vision Zero. Vision Zero, 2018. Retrieved from https://visionzeronetwork.org/project/communications-strategies-to-advance-vision-zero/. Accessed on 11 April 2019