Racially-biased policing in Oakland (updated with 2019 data)

The Oakland Police Department is legally required to provide racial data on police stops. But they’re not required to make it easy. But they finally released their report.

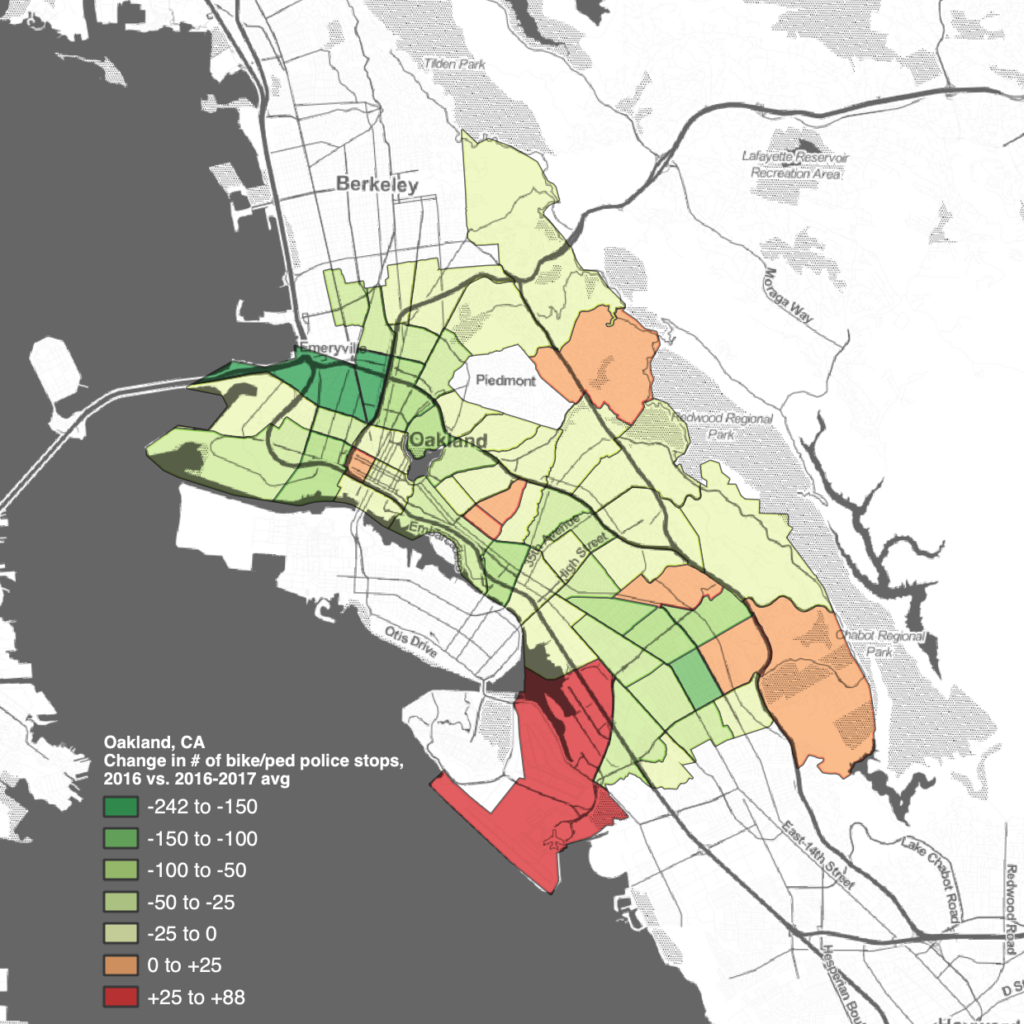

We don’t have detailed public data on where the stops are occurring, only the police beat. I did some hacky stuff to estimate the racial composition of each police beat using Census data, and tested whether the stops were proportional to the racial makeup. As you might guess, the answer is “no.” In 2019, the problem was marginally better, but it’s still a problem.