Exploring geographies

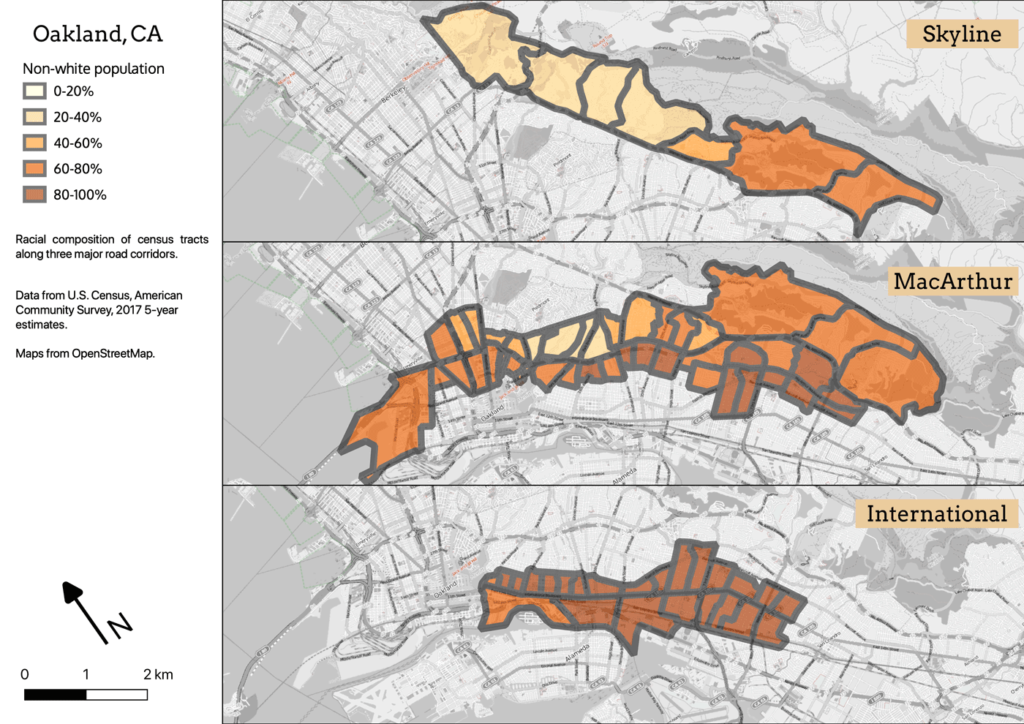

I love how cycling changes my experience of moving through the city; it’s part of what’s informed my Bike Lab work from the start. And I love sharing that experience with others, which is why I’ve been running urban geography rides for WOBO. The urban stories of investment and disinvestment, advantage and disadvantage come to light as you ride through neighborhoods at a human pace. This week, WOBO referred to me a wonderful opportunity to lead a group of officials and planners from Portland who were in town to meet with local groups and learn about our planning issues. I took them off into West Oakland.