The Holy Grail of community economic development is “development without displacement”: reinvestment in decayed neighborhoods which can provide long-time residents with new opportunities, without forcing them from their homes. It’s hard to achieve in a market-driven society, especially one where home ownership rates and household wealth are as wildly disparate as they are here in America. But it’s not impossible. Here are six U.S. cities where the neighborhoods around MLK Way are increasing both in income and in Black population.

| Total population change, 2000-2017 | Population change, Black, 2000-2017 | Real median income change (2018 $), 2000-2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charlotte, NC | 8,096 | 1,270 | $52,915.51 |

| Louisville, KY | 1,387 | 228 | $344.69 |

| Memphis, TN | 2,318 | 725 | $5,785.05 |

| Phoenix, AZ | 19,657 | 2,335 | $595.78 |

| St. Petersburg, FL | 11,015 | 2,254 | $688.64 |

| Washington, DC | 7,176 | 1,561 | $11,132.69 |

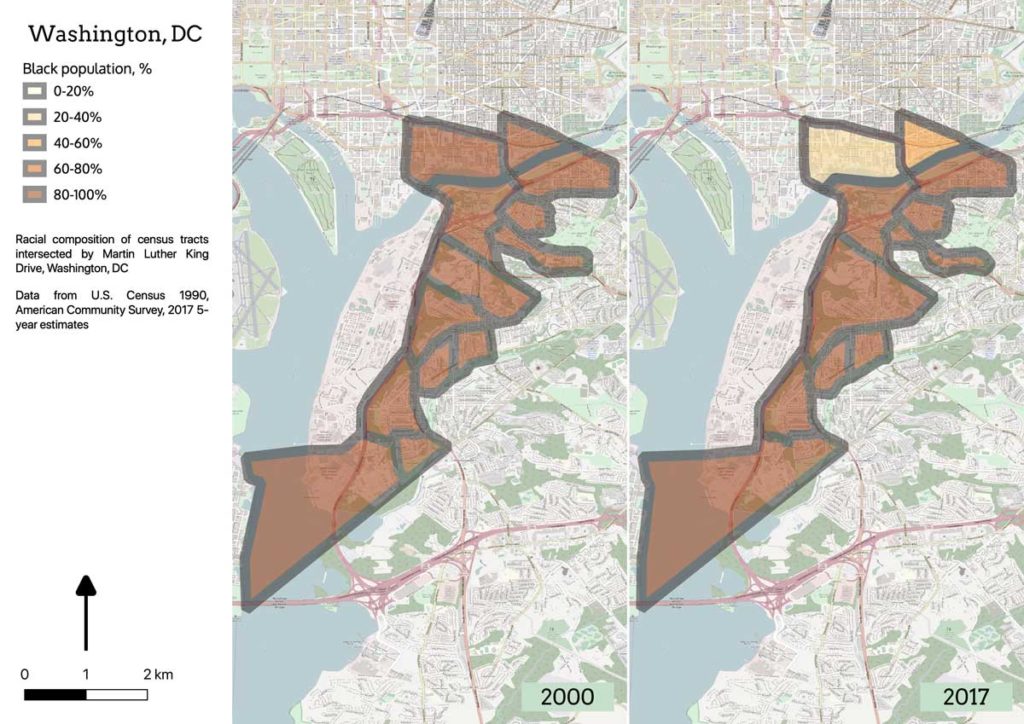

Perhaps the most promising of the stories is in southeastern Washington, DC. These tracts were 94.1% Black in 2000, and in the middle of the pack in median income in the study cities. Given the high cost of living in the nation’s capital, this neighborhood was poor.

In the ensuing years, many Whites have moved in, primarily on the north side of the river. Capitol Hill is just north of those tracts. But while the proportion of Black people in these tracts has fallen to 81%, the absolute number of Black people has actually risen.

More analysis is needed to determine what’s going on for the people living south of the river. It could be that more affluent Black people are displacing poorer Black people. It may be that all of the increase in median income is happening north of the river, and the southern neighborhoods are still poor. So it would be premature to say that this a policy success. But it’s safe to say that this is what policy success looks like; neighborhoods where people are able to stay in their homes (if they want to) while experiencing less crime and getting better access to job opportunities and education.

That airport on the other side of the river (Reagan National) is in Arlington, right next to where Amazon is building its HQ2 campus. How will the influx of tech workers affect these nearby neighborhoods? Presumably the median incomes will rise further, and White and Asian populations will grow relative to populations of Black people. Are there protections in place (home ownership, rent control, community land trusts) to allow long-time lower-income residents to stay if they want to? Or will they be re-segregated out into the exurbs?

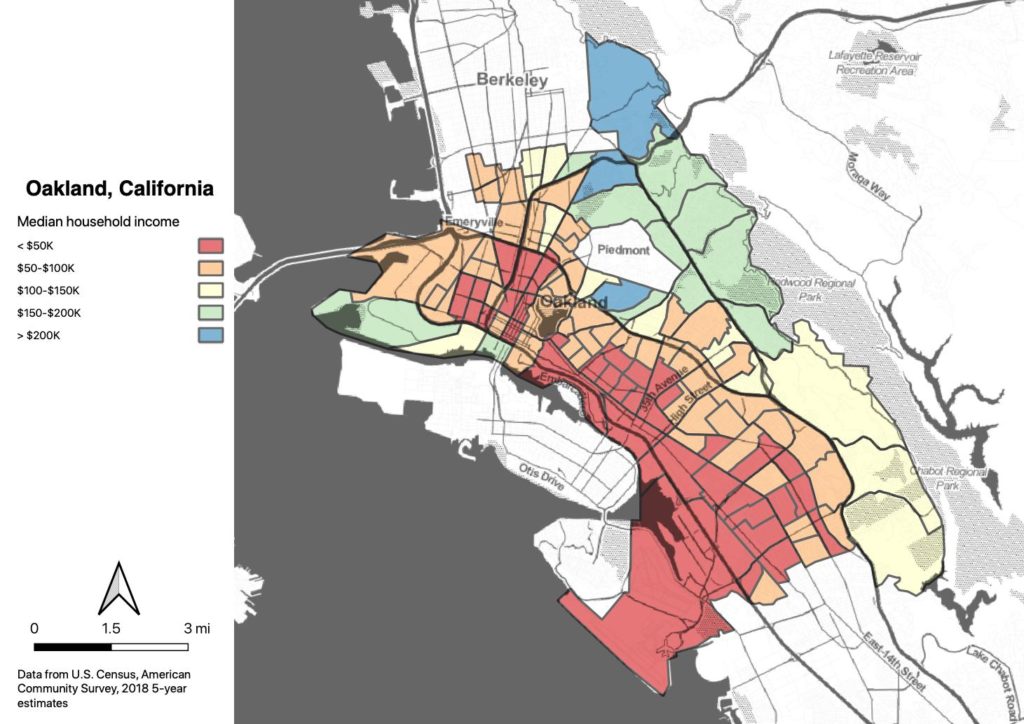

Equity concerns still exist in places developing without displacement. Even when residents are not being displaced spatially, they may be displaced culturally. New, more affluent residents, from different cultural backgrounds will bring with them new institutions which change the feel of the neighborhood. The new residents may also object to long-standing cultural practices, as BBQ Becky (a Stanford-educated chemical engineering PhD) famously did at Lake Merritt in Oakland. Lake Merritt also saw cultural conflict over the Samba Funk drummers who regularly play there on weekends, and a complaint was filed about loud gospel music at a church in West Oakland.

I think Oakland has done a pretty good job responding to these complaints. Many people came to Pleasant Grove Church’s defense (the city declined to fine them), Libby Schaaf invited Samba Funk to play her out of the chambers at her State of the City address, and the BBQ’n While Black event at Oakland celebrated the long-standing BBQ culture of the city. But in the long term, culture will change, and a city that cares has to grapple with figuring out how to honor long-time communities without sealing them in amber.

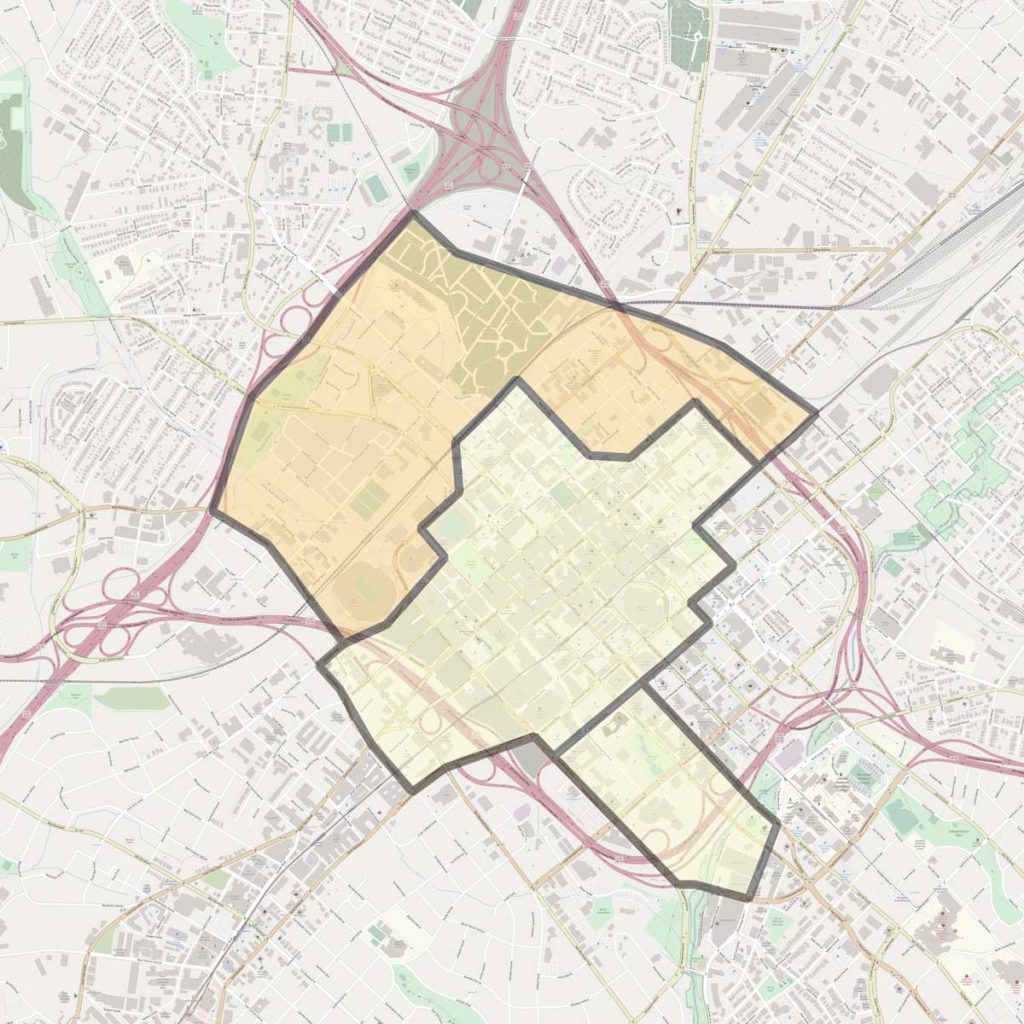

One more map from Charlotte, which was also part of my field work. Charlotte is one of the fastest-growing cities in the country, and the amount of construction going on when I was there in 2016 was astounding. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard happens to be right in the middle of the financial district downtown, which explains the huge increase in median income; Charlotte over the past 20 years has become the biggest banking center in the U.S. outside of New York. The presence of Johnson C. Smith University, a HBCU in the northern tract here, probably explains the stable (but still small) Black population.

Only two of the six cities here (Washington, D.C. and Memphis, TN) really qualify as representing significant development without displacement. Memphis, of course, is where Reverend King was shot, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Avenue is only a few blocks away from the location, which is now the National Civil Rights Museum memorializing his life and struggle.

It is ironic that Memphis is one of the few places where Black people who live near the street named for Dr. King seem to be doing well today. What can we learn from Washington and Memphis that we can use elsewhere to counteract the forces of racism and the logics of capitalism?

One thing is clear: the struggle never ends.