Public-private partnerships require compromises. The goal of the public entity (the public interest, ideally) is inherently in tension with the goal of the private entity (profit, explicitly). The agreements made between the two codify a set of compromises each side is willing to make to work together.

These partnerships usually include severely imbalanced power relationships. Multi-billion dollar international conglomerates do not negotiate on an equal basis with individual cities, so cities often end up compromising far too much in the process of getting a contract signed.

Compromises on terms, such the cost of a service or the division of contract responsibilities, are natural in such negotiations, but I am concerned with compromises on principles. Oakland’s contracts include provisions for civic principles such as equity and accessibility—principles which the private entity does not care about, and will not deliver except under contractual obligation—and unless we write real requirements into the contract, and enforce them, they will be ignored.

There are two ways cities compromise their principles in public-private partnerships: bullshit requirements, and bullshit enforcement.

Bullshit enforcement

This came up during the May BPAC’s presentation on e-scooter operators in Oakland. Oakland announced three new scooter operators in October 2020; two of them had representatives at the meeting (Spin and LINK). Kerby Olsen, Oakland’s New Mobility Supervisor, presented about the program, focusing on the efforts to require scooters to be locked to bike racks. During his presentation he mentioned that the city is not enforcing the equity provisions of the contract, because the vendors have seen a 75% drop in ridership. Both Spin and Link noted that they’re not in compliance: the Spin rep said that they want to work with communities to find out where to put the scooters, and the Link rep said, basically, that they’re small and they can’t afford to.

That’s 100% bullshit.

In my neighborhood, Spin didn’t have to ask people to figure out that they should put scooters at Macarthur BART and Cato’s Ale House. It’s not hard. Scooters would definitely get used at Eastmont Transit Center, or the East Oakland libraries or schools.

Also, this contract was awarded six months into COVID, so everyone already knew about the drop in ridership. If COVID makes you unable to meet the equity provisions, you aren’t capable of fulfilling the contract, and if the city is awarding the contract to vendors incapable of meeting the equity provisions, and if it falls to enforce those provisions, the city is complicit in perpetuating inequity.

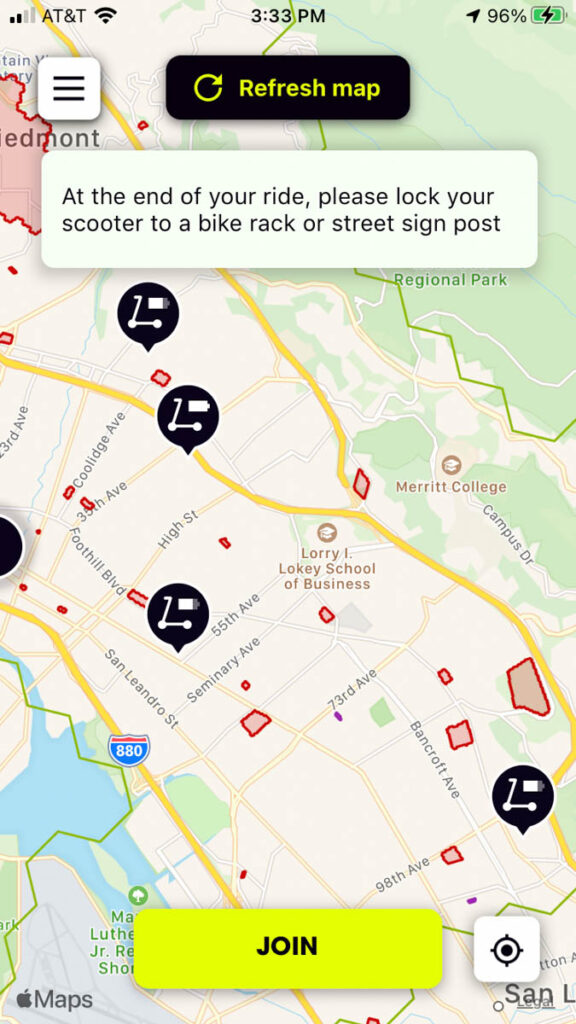

One BPAC commissioner who is critical of the program told me that they didn’t think there was a single scooter available in District 6 (East Oakland) or District 7 (Deep East). That’s close to correct: at the time I checked the apps, there was exactly one scooter in East (at 55th and International) and one in Deep East (at Foothill Square, end of the AC Transit 57 bus line). Those were obviously not put there by the vendors.

There also appear to be a grand total of zero three-wheeled adaptive scooters.

It is not Oakland’s problem that companies like Spin (a division of Ford Motor Company) do not have a sustainable business model. Even more, it is not our problem that providing equitable and accessible micromobility is less profitable than providing micromobility for abled people in affluent neighborhoods. If we actually believe that equity and accessibility are important principles, it’s on us to enforce the contract requirements, all the time, and not only when it’s convenient for the vendors.

If you can’t meet the requirements, get out of Oakland.

Bullshit requirements

Unfortunately, the equity and accessibility requirements in most contracts are so weak that we never get to enforce them in the first place, and the e-scooter contract is a perfect example. Here’s its requirement for equitable distribution:

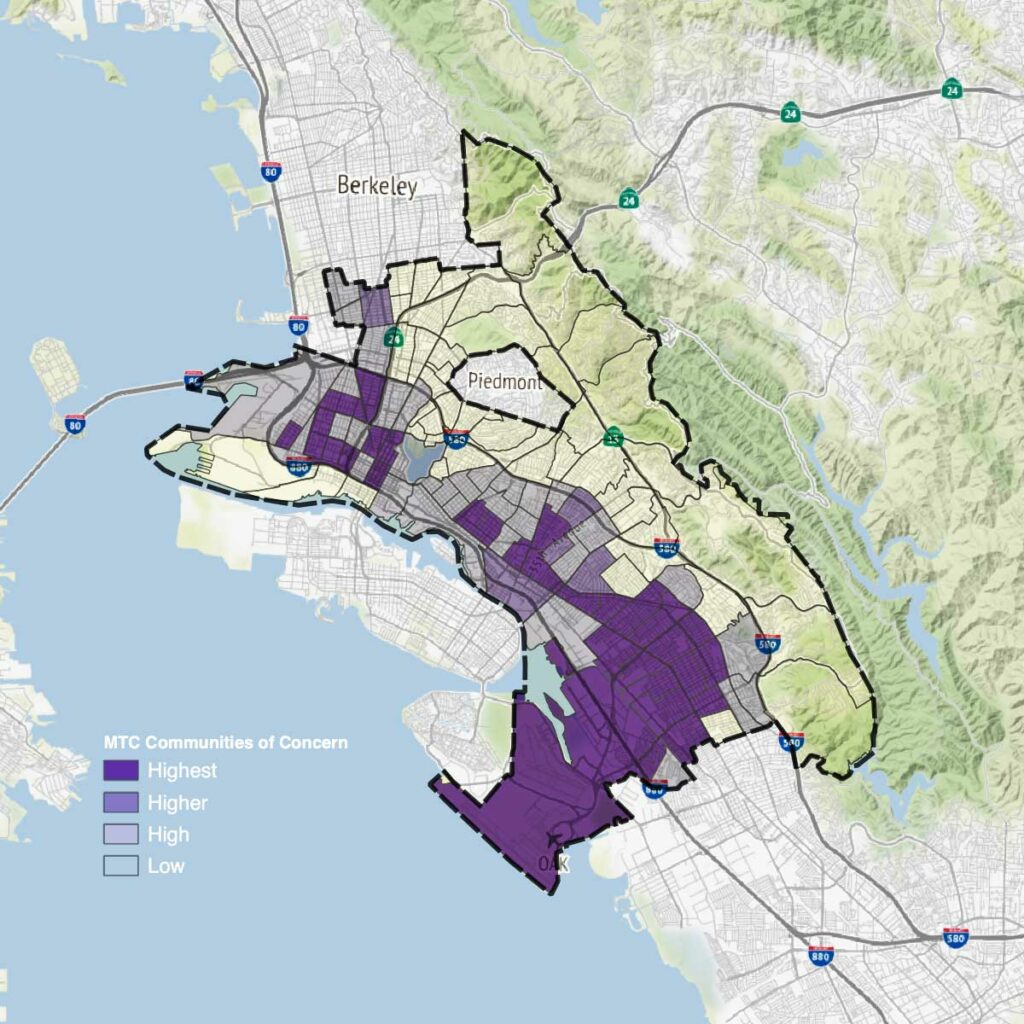

Dockless Scooters should be distributed equitably throughout Oakland. More than 50% of Scooters must be deployed in Oakland’s Communities of Concern, as designated by the Metropolitan Transportation Commission.

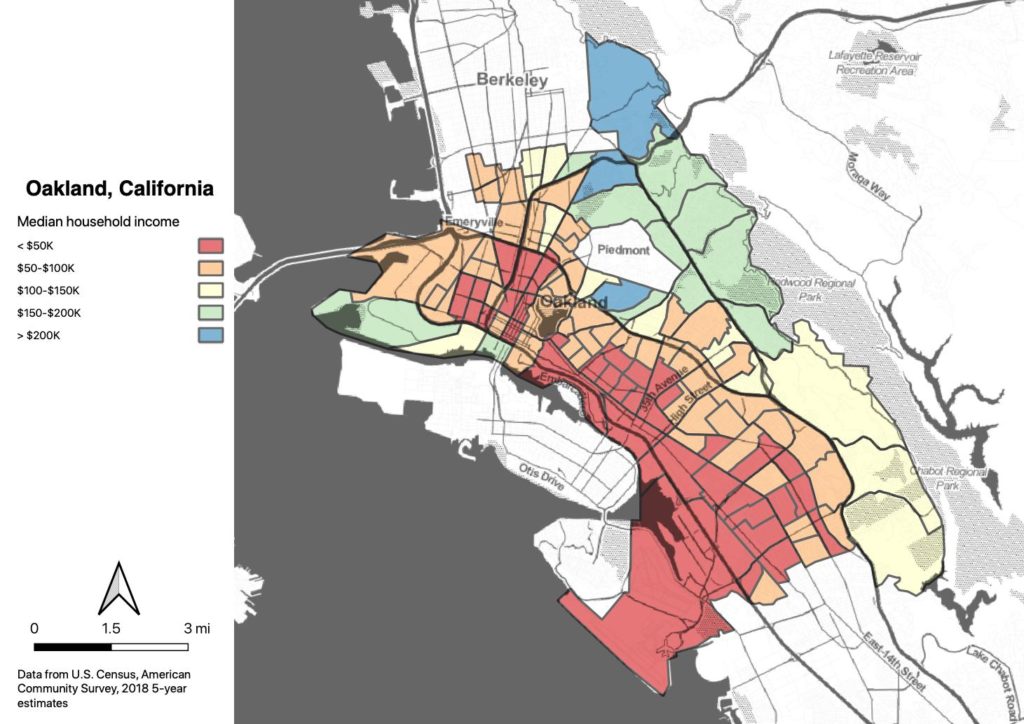

50% of scooters in Communities of Concern sounds pretty good, right? Until you actually look at MTC’s Communities of Concern map.

For whatever reasons, MTC’s Communities of Concern map includes most of Oakland, including downtown, Uptown and Lake Merritt. It would be impossible for a for-profit scooter vendor to fail to fit 50% of its scooters into this map.

It’s a bullshit requirement, and everyone involved knows it.

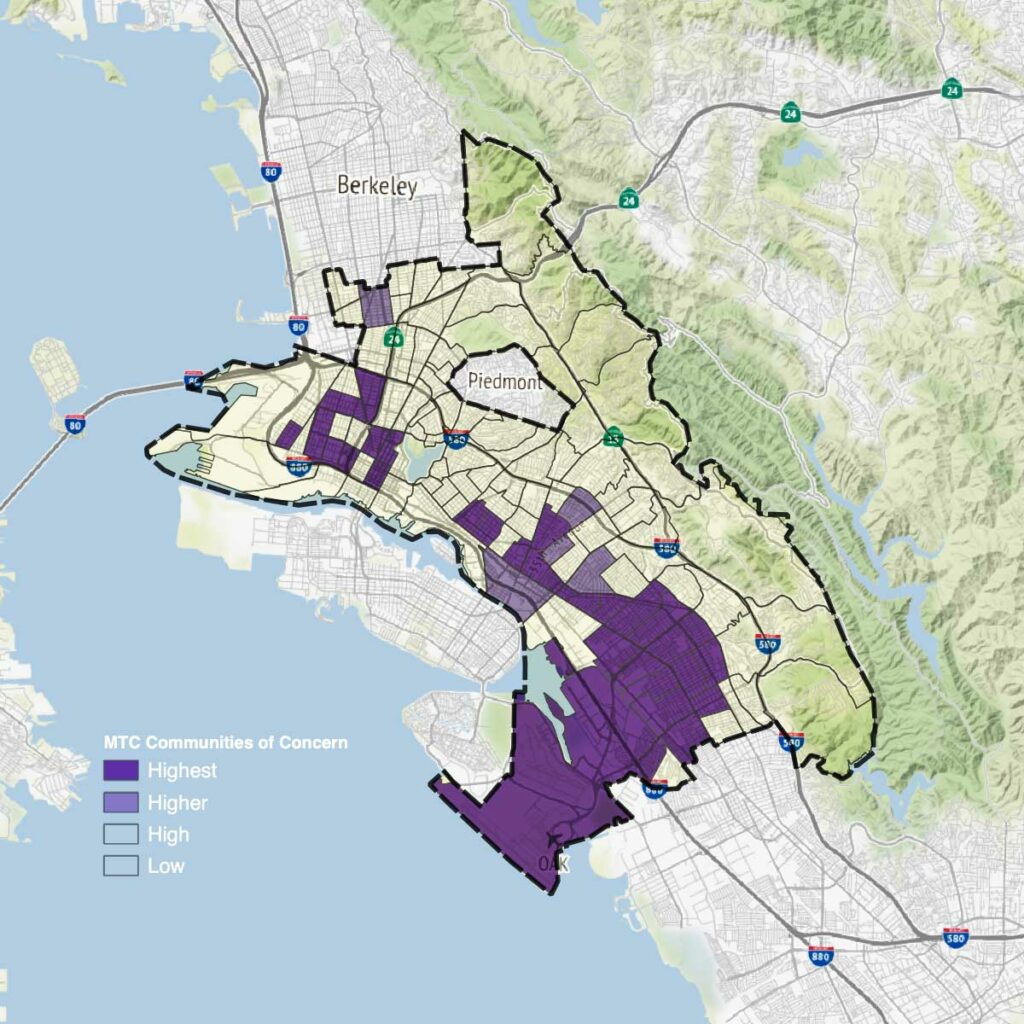

We could make this requirement meaningful by requiring 50% of scooters to be located in MTC’s Higher or Highest Concern areas. Here’s that map:

Vendors wouldn’t want this. It might be less profitable. But it could have a real effect on transportation inequities in Oakland, which the current requirement doesn’t.

The scooter contract also has bullshit accessibility requirements. Here’s the accessibility clause:

(1) Operators must provide Adaptive Scooters for persons with disabilities. The total

percentage of Adaptive Scooters shall be based on expected need, performance,

and usage.

(2) If the Operator is unable to deploy Adaptive Scooters at the time of permit issuance,

a plan must be submitted to the Oakland Department of Transportation within three

months of permit issuance detailing a timeline for incorporation of shared Adaptive

Scooters.

Both of these are total bullshit. Section (1) doesn’t specify who decides what “expected need and usage” is, which effectively means the vendor makes the call. They can say, “we don’t see much demand for adaptive scooters,” so there’s nothing to stop them from ignoring the requirement indefinitely, which is what Bay Area Bike Share is still doing, six years into their contract. Bay Area Bike Share canceled even their half-assed program where you could borrow a trike to ride around Lake Merritt on Saturdays. That was two years ago.

(BORP, which was paid to operate that program, still runs a great adaptive cycling program at the Berkeley Marina, entirely on grant and donation funding. Don’t tell me that Lyft, market value $18.4 billion, can’t afford it. Bullshit.)

Section (2) specifies a timeline for providing a plan, but not a timeline for providing the service. The vendor can (and will) give us a line of crap about how they’re investigating potential options for adaptive scooters, and they are working with engineers to develop a prototype, and they plan to pilot it as part of their Phase 2 rollout, and they hope to deploy by Q2 2023. If they haven’t gone out of business by then.

Again, this is bullshit and everyone involved knows it. Especially when they know we don’t intend to enforce even the weak requirements we’ve included.

Here’s what a non-bullshit accessibility contract clause might say:

(1) Operators must provide Adaptive Scooters for persons with disabilities. At least 5% of the Operator’s total fleet must meet the section (6)(a) requirements for Adaptive Scooters.

(2) If the Operator is unable to deploy Adaptive Scooters at the time of permit issuance, a plan must be submitted to the Oakland Department of Transportation within three months of permit issuance detailing a timeline of no longer than one year for incorporation of shared Adaptive Scooters.

It’s totally doable. So why aren’t we doing it?

Conclusion

OakDOT’s Shared Mobility Team has drafted a set of Shared Mobility Principles. They’re not bad. They include:

Racial Equity

The communities of East Oakland, Fruitvale and West Oakland, where high number of Latino, Black and low income residents live, are underserved by transportation options, including shared mobility. Shared mobility services should be designed in a way that maximizes benefits and minimizes burdens while giving communities opportunities to have decision making authority. Shared mobility services should include these communities and their common destinations in their service area, identify and reduce barriers to access, ensure that their service does not allow or perpetuate discrimination based on race, and provides health and economic benefits.

Equitable Access to services

Shared mobility services should provide greater physical, cultural, financial and digital access to transportation options for low income communities of color and persons with disabilities.

If you’re going to compromise these principles in writing a contract, and then compromise them again when enforcing it, you undermine the purpose of your statement. You essentially say that, “yes, we kinda think equity and accessibility are important, but they’re not as important as helping billon-dollar corporations make money in Oakland.”

The challenge to everyone who shares these principles is to enact them in every aspect of our jobs. Whether you’re a department head, an individual contributor or a contractor, you can insist on equity and inclusion in the work that you do. These contracts require the work of dozens of mostly well-meaning individuals; the bullshit will stop if enough of us refuse to compromise.