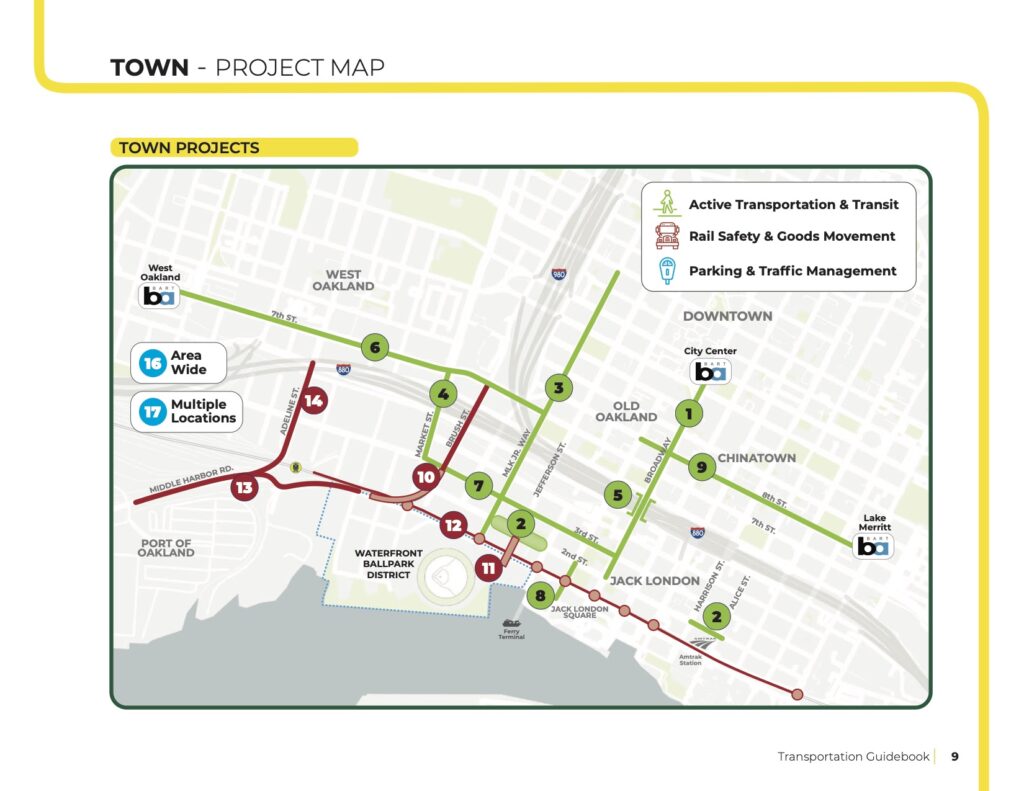

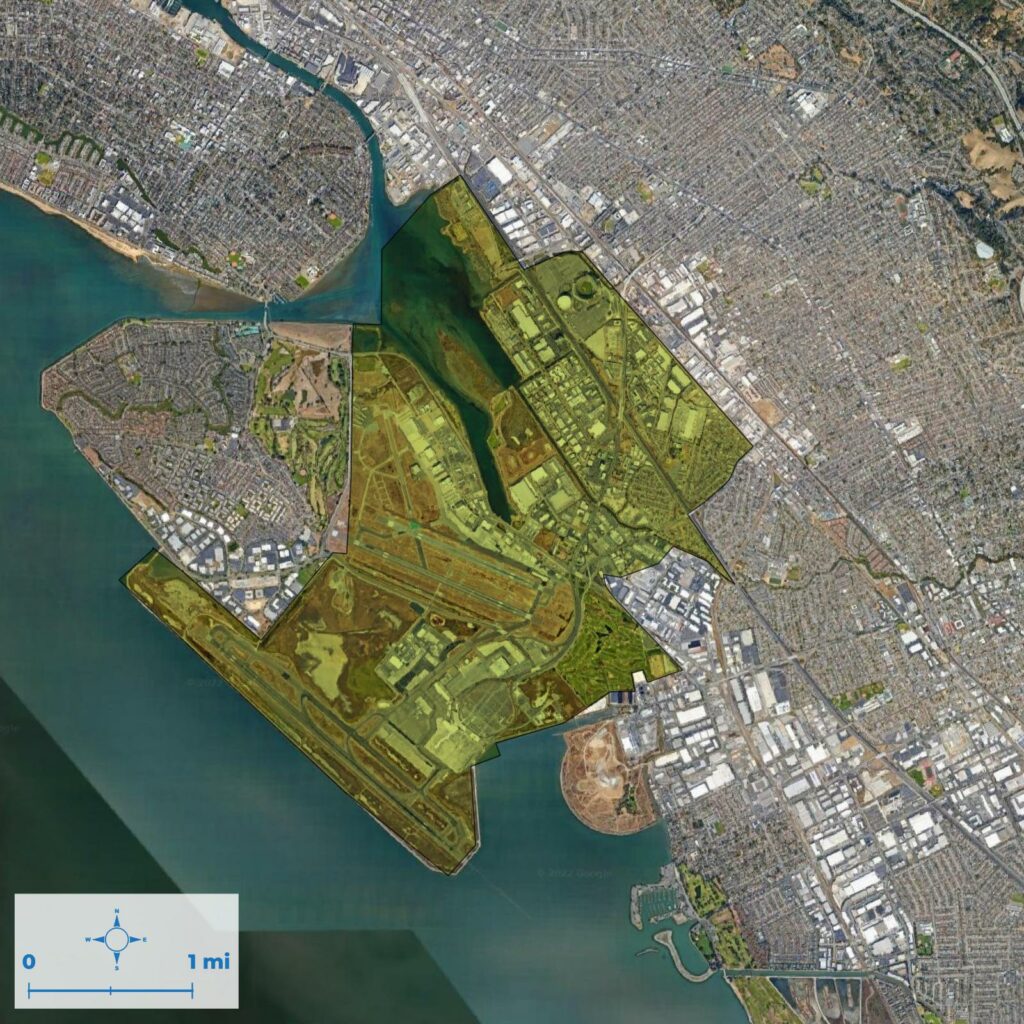

I got into a good rant at Oakland BPAC this month, and I think it’s worth fleshing out here. The topic was the Transforming Oakland’s Waterfront Neighborhoods (TOWN) project, the city’s attempt to give away hundreds of millions of dollars in support of the cynical and extractive effort to let a billionaire enrich himself by building 3,000 luxury condos at Howard Terminal. Oakland’s planning to pay for “off-site infrastructure” to support the project, and a ton of infrastructure would be necessary, because to get to the site you have to cross 12 lanes of freeway and an at-grade double-tracked main line railroad serving a major seaport.

It so happened that the BPAC meeting was the same day that Oakland was notified that it once again failed to get Active Transportation Program funding for two East Oakland projects, on Bancroft and 73rd. I’m also currently working on community engagement for the city’s Capital Improvement Program, and part of what we heard from East Oakland residents is frustration that their waterfront access projects have been sidelined: the San Leandro Creek Greenway has been indefinitely shelved because of a dispute with Union Pacific over a spur rail line, the East Bay Greenway has made no progress in Oakland south of 85th because no one wants to commit to maintenance, and we’re still years away from anything happening on 66th Avenue by the Coliseum.

[Speaking of the Coliseum: We already have a bike/ped bridge over the railroad tracks there, but the Coliseum Authority refuses to keep the gate open. Can we do something about that, please? Do I just need to bring an angle grinder the next time I’m down that way?]

Anyway, I was already in a pissy mood, and reading the agenda packet about this project, I kept getting more and more annoyed. The TOWN presenters (formerly named “TOWN For All” before people called bullshit on that) didn’t even make an effort to address the realities of the proposal; this packet is pure marketing. Here’s some of the manure being shoveled:

“Equity analysis”

The FAQ section of the presentation includes:

Were these projects informed by an equity impact analysis?

Yes. The projects underwent a racial equity impact assessment to identify the most effective projects that aim to reduce existing transportation disparities between the surrounding neighborhoods and more affluent neighborhoods in Oakland.

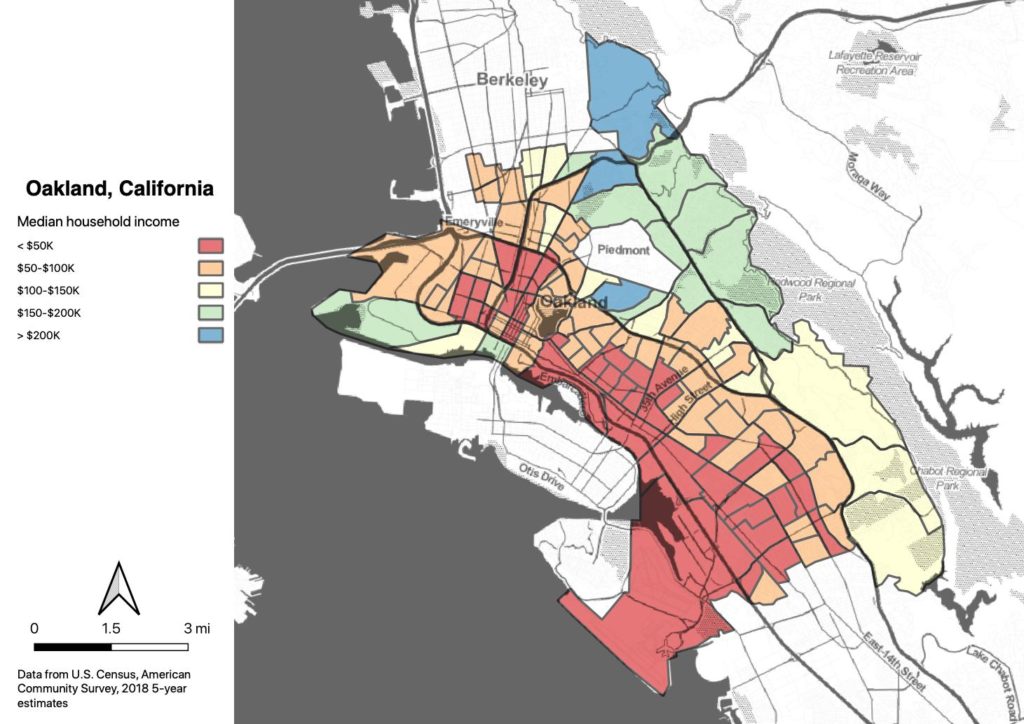

Here’s the project area:

Tract 983200 is 58% white. Median income is $161,000. Among the few people who live near Howard Terminal, the median income is is even higher ($195,000). These are two of the whitest and wealthiest neighborhoods in all of the flatlands.

Connectivity from the surrounding neighborhoods to the waterfront is basically fine. There are five streets in this area (Jefferson, Washington, Jackson, Oak, and Madison) which pass underneath the freeway as low-traffic streets with bike lanes.

Here’s tract 409000, where the Scraper Bike Team has 4th and 5th graders riding to the waterfront from Brookfield Elementary.

This neighborhood is over 98% non-white. Median income is $53K. And connectivity to the waterfront is abysmal, available only on freeway-scale roads like Hegenberger and 66th Avenue.

There is no way an honest equity analysis could conclude that investing in access to the waterfront at Jack London Square is more equitable than investing in access to the waterfront in East Oakland. Jack London Square might be more profitable, or more popular, or easier to get grants for, but there is no way it’s more equitable.

Fallacy or horse pucky?

Among the fallacious claims made in the presentation is:

Q: Are the TOWN projects diverting resources from other areas across the City?

A: No. Staff time spent on TOWN projects is funded by project developers and State and Federal grants, thereby preserving resources to allocate to other priority projects. Additionally, with the establishment of a new Major Projects Division, new staff are being hired to focus exclusively on TOWN and other significant infrastructure projects, so that existing staff can remain dedicated to ensuring that ongoing priorities such as paving and traffic safety projects move forward in a timely manner.

Grants require external capacity. I’ve worked with a lot of grant-receiving organizations, and I’ve yet to see a grant that pays for itself. For one thing, grants don’t pay for grant-writing, and good grant writers are expensive. For another, this BPAC presentation was being given by two existing staff who obviously had taken time away from their ongoing priorities to prepare and present it. OakDOT couldn’t send new staff to do the presentation because OakDOT has for years been unable to hire enough project management staff to keep up with its existing demand. As this Major Projects Division gets built, its 13 FTE will require HR services, IT services, management and leadership attention, which will all be in competition with the rest of OakDOT.

But more to the point, we’re making a choice to build this specific organization to develop these kinds of grants specifically for Jack London Square. We could instead choose to develop a Major Projects Division to work on grants for East Oakland, so why are we choosing to develop it for Jack London Square instead?

The love of a lousy buck, is why. Institutional capture is a feature of capitalism, I get it. But if you’re working on behalf of real estate investors, at least be honest about it.

Failing on its own merits

I’ve known all the above crap about this project for a while. What I hadn’t fully understood prior to this presentation is how bad the infrastructure proposal is on its own merits.

As I mentioned above, the walk and bike connectivity to Jack London Square is basically not a problem today; Broadway is a mess, but alternate streets within a couple blocks on both sides are entirely usable. They’re not particularly attractive because they pass underneath the freeway, but putting sparkly lights in the underpass won’t change how accessible they are—it just might change who is willing to walk that way, which is the real point of the project.

Building 3,000 condos at Howard Terminal would create thousands of new daily trips (26K, per the presentation). That kind of volume is incompatible with at-grade crossings of the rail lines, which are actively used by passenger trains and by the port. Sometimes a freight train has to block all the access to the waterfront for 10-15 minutes to back up into the rail yard. To deal with that issue, the project looks to grade-separate the crossings.

Because it’s at the port, the train crossing can’t be elevated or buried, which means bikes, pedestrians and cars will need bridges over the tracks. The project proposes to:

- Build fences all along the rail lines

- Add a bike and pedestrian bridge where there’s currently an at-grade crossing on Jefferson

- Add a cars-only overpass, landing at Embarcadero and Brush Street

Wait, what? This is increasing access, for who?

Dedicated bike/ped bridges over rail lines suck. Sometimes they’re the best you can do, but they’re almost never enjoyable or effective. They have to be high to clear the rail lines, and the slope has to be gentle for ADA access, so you wind up having to corkscrew them or take up enormous amounts of space. The new bridge at Bay Street in Emeryville is about as good as it can be, and it’s still not great. I can’t imagine choosing to take that route on a bike if I had an alternative.

Fences along the waterfront suck, too. Here’s what it looks like now at the Amtrak station. The whole waterfront would look like this under the proposal. It’s ugly and it reduces access; there’s a reason the presentation deck doesn’t include a rendering of it.

[Editor’s note: I once missed a train because of this fence.]

And whoo, that third point. A new freeway ramp exclusively for cars, high enough to clear the rail line. I can’t imagine that they can land it on the estuary side of 880, so it will probably have to cross the freeway, too, and land around 8th Street. Just what West Oakland needs, another concrete superstructure. Not surprisingly, the presentation deck doesn’t have a rendering of that, either.

I was entirely ready to oppose this project based on its disingenuous claims of equity. I was a bit surprised to realize that even if you set the equity concerns aside, it still looks like a terrible idea.

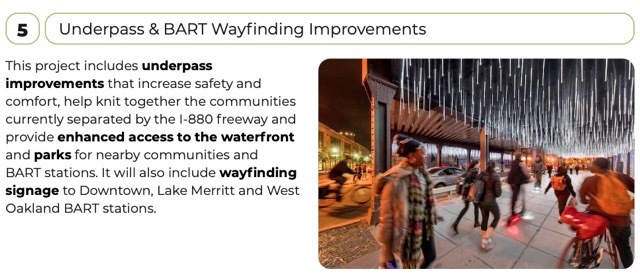

Sparkly lights

I expect that the findings of the program’s ersatz equity analysis rest on the proximity of the Acorn housing projects in West Oakland. Acorn was built post-WWII, partly as a place to house those displaced by other West Oakland infrastructure projects like the Grove-Shafter Freeway, BART, and the USPS sorting facility. The people living at Acorn today are legitimately disadvantaged; it’s 60% Black, with a median income of just $31K. But this project does nothing for those residents. Here’s a slide from the presentation deck:

The image is from Washington DC, where an underpass decoration project, in northeast DC’s rapidly gentrifying “NoMa” neighborhood, debuted to great fanfare in 2018. This installation, titled “Rain”, is on M Street; there are several others.

[Editor’s note: I am not sure what NoMa stands for. But I am sure it’s an invention of real estate assholes.]

Shockingly, adding sparkly lights to the underpass didn’t address the issues of the marginalized people living in northeastern DC. It took about 4 months for the encampments, which had been cleared out to make way for the fancy art, to return to the underpasses. In 2021 the city returned to clear it out again, only to be stopped when a bulldozer ran over someone still in his tent.

That people in the Acorn development don’t have good access to Oakland’s waterfront has nothing to do with how the underpasses are decorated; sparkly lights are not going to help them. Jack London Square doesn’t have much to offer for anyone not spending money; racial capital has no use for poor, criminalized Black people.

At last, DC appears to have come up with a solution to the encampment problem.

Conclusion

What keeps us going, ultimately, is our love for each other, and our refusal to bow our heads, to accept the verdict, however all-powerful it seems. It’s what ordinary people have to do. You have to love each other. You have to defend each other. You have to fight.

Mike Davis, author of City of Quartz

As I’m writing this, many colleagues are eulogizing Mike Davis, so it feels appropriate to be railing against the city’s relationship to racial capital. I find it shameful that Oakland is sending out good people to give presentations like this. Do the presenters really believe that this project meets equity goals and that it won’t take any resources from other work the city is doing? They have to know they’re bullshitting. Maybe they don’t care. Or, more hopefully, maybe they know it’s wrong, but they feel trapped in their situation and have to go along to keep their job. That’s exactly the situation that racial capital produces and exploits.

Mike Davis called on us to recognize our shared humanity. We do not owe anything to the grand vision of a corporation or funder or a designer (or, God forbid, John Fisher); we owe service and support to each other as human beings. Whatever project you’re proposing or reviewing or participating in or assigned to, think about: What are the impacts? Who benefits? Who is disadvantaged?

And if you think it’s wrong, are you going to stay in the cushy job, for a lousy buck? Or are you going to do something about it?