After doing some crunching this week on data about rapidly-gentrifying Valencia Street in San Francisco, and finding that residential density is actually dropping in the neighborhood despite new housing construction, I wondered whether the same phenomenon could be found elsewhere in the country. I didn’t have to wait long for another case study, as Lynda Lopez and a number of other peeps I follow from Chicago posted about Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s ill-considered statement about “vibrancy” in Pilsen, a gentrifying neighborhood west of the Loop. Lightfoot was speaking at an event sponsored by The Economist (of course).

I will preface this analysis by saying I don’t know Chicago well, so my conclusions are based on statistics rather than lived experience. And in particular, neighborhood boundaries are social constructions, so not everyone will agree with what defines a neighborhood, and the U.S. Census, where I get my data from, really doesn’t care about neighborhood boundaries. So the area I’m using for the map and data won’t necessarily fit with what people on the ground might define as Pilsen.

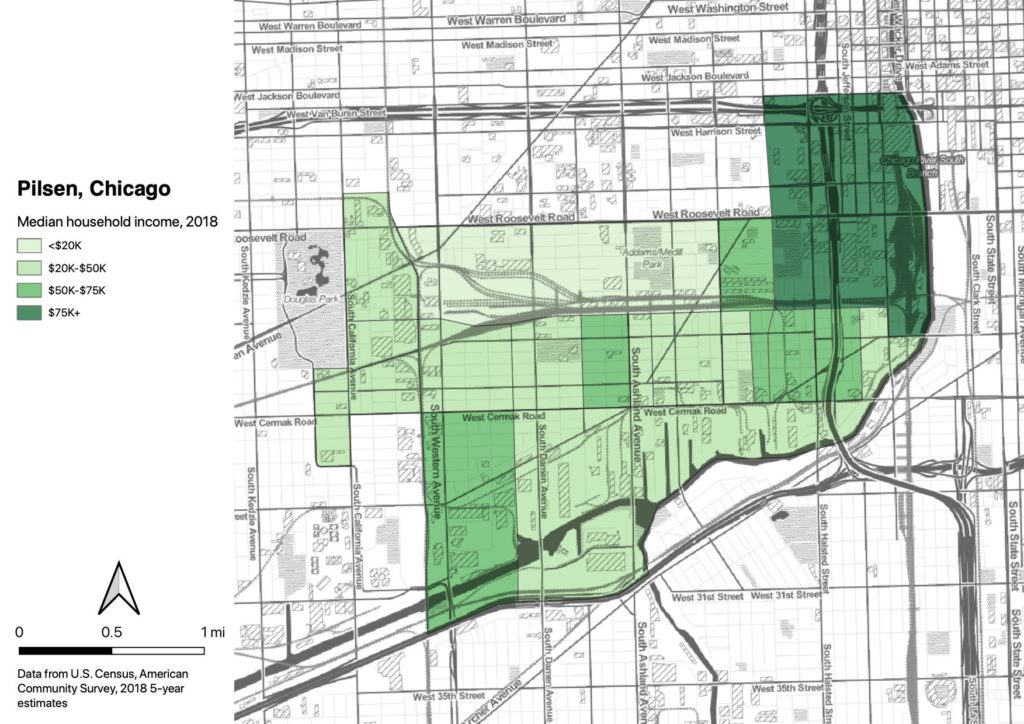

Below is the area I’m working with, in 2018, by median household income.

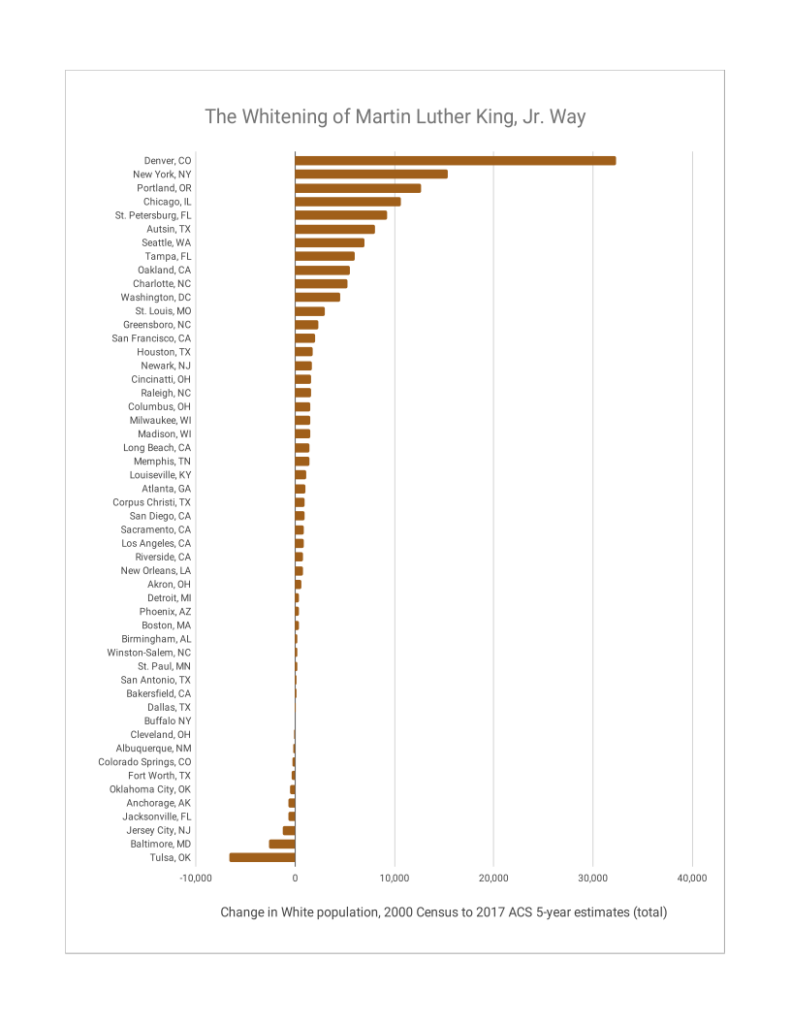

20 years ago, Pilsen, like San Francisco’s Mission District at the time, was predominantly working-class and Hispanic. Since then, Hispanics have been displaced by affluent Whites. The Census tract boundaries have changed, making one-to-one spatial comparisons more difficult, but here is the summary data for the district:

- A bunch of housing has been built since 2000 (net gain of ~1,500 units).

- Hispanics have been substantially displaced: there are ~12,500 fewer Hispanic residents than there were in 2000, a drop of 30%, and there are ~7,500 new White residents, a 207% increase.

- Inflation-adjusted median household income has risen 46%; in tract 8419 (East Pilsen) it’s now over $116K.

- Total number of commuters has risen 37% while the total number of residents has fallen 7%.

The numbers aren’t quite as dramatic as in the Mission, but the story is the same: affluent Whites living alone are displacing working-class Hispanic families, with the result being a net decrease in residential density despite new infill housing construction.

Mayor Lightfoot’s comments, about Pilsen being a “vibrant, thriving neighborhood,” belong to the same New Urbanist, “creative class” philosophy which celebrates Valencia Street. “Vibrancy” is one of New Urbanism’s most prevalent tropes; what activities appear “vibrant”? The proportion of residents who commute to work has risen from 33% to 49%, and there are fewer residents anyway, so it’s likely that the street sees far less activity during the day than it once did. If you think a fancy cocktail bar is more “vibrant” than a taqueria, what do you mean by that term? And, exactly who is “thriving” in Pilsen? Surely not the ~14K people of color who’ve been displaced.

Here’s a tweet which came up a couple weeks back from Annie Fryman, Scott Wiener’s policy analyst. (Wiener, for any non-Californian readers, was the San Francisco supervisor for the district which includes Valencia Street, and now is in the state legislature trying to pass bills pushing market-rate infill housing).

This thread neatly encapsulates the vision of the city as a place that affluent Whites can colonize (explore and lay claim to). Diversity manifests primarily in aesthetics and cuisine (Fryman’s list was amended to include Ethiopian and boba). New Urbanists may not care about building a city where working-class Latinos can live, but they definitely want to be able to buy good tacos. In this vision, “thriving” neighborhoods are the ones where White people spend money.

And while I object to that vision, that’s not even the point I’m making here. What I really object to is New Urbanism being sold as a climate solution. A dense city will produce less carbon than a sprawling one, all else being equal, but in Pilsen and in the Mission, gentrification is actually reducing the density of the city, creating more resource consumption and more carbon emissions.

I’d like to run this analysis for gentrifying neighborhoods across the U.S, if I can figure out how to scale up the geospatial number-crunching. (The definition of “gentrifying neighborhood” is the hard part.) But I’m pretty confident that low-income family groups emit a lot less carbon per capita than high-income single dudes. If you really want to work on urban policy as a climate response, the first thing you need to do is to protect the existing working-class residents from displacement. They’re not the ones emitting carbon.