Oakland’s Department of Transportation continues to work towards aligning city practices with the values expressed in its Geographic Equity Toolbox. The latest example is a report on the research and community engagement OakDOT led for a now-adopted Community-Led Traffic Safety Pilot program.

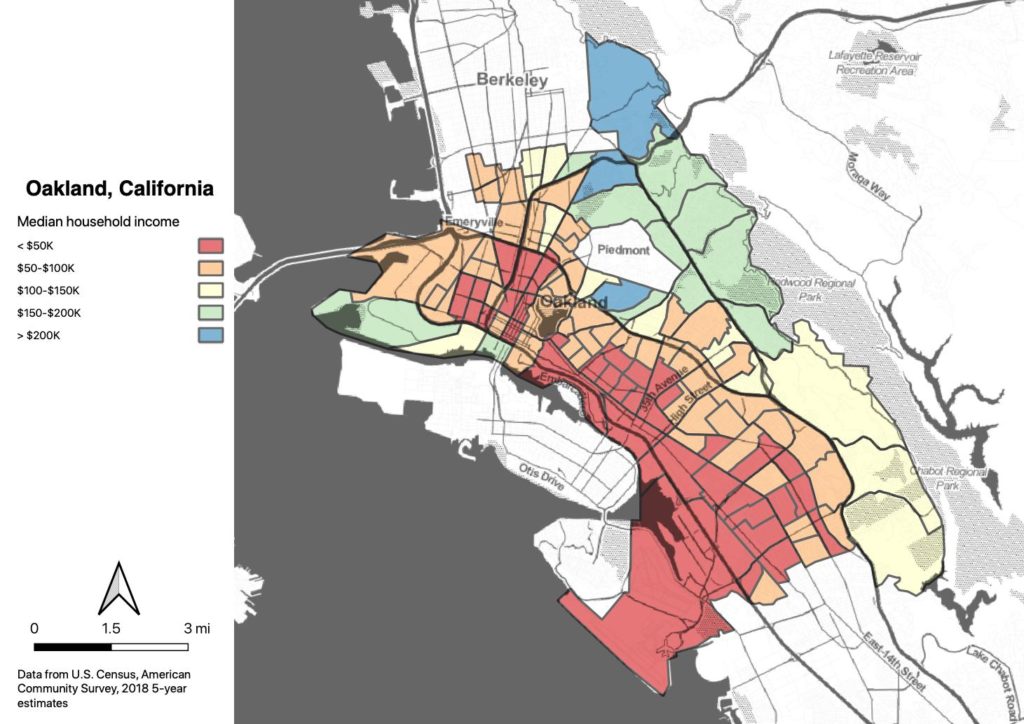

The Geographic Equity Toolbox attempts to address the inequitable cycle of new investment following old investment, and new disinvestment following old disinvestment. Policies and funding mechanisms are structured to advantage neighborhoods with more resources over those with less. Many OakDOT staffers want to grapple with their roles in supporting those structures, and the toolbox can be used to investigate a project’s equity implications, and counteract some of those structural forces.

![OakDOT Geographic Equity Toolbox A map of the city of Oakland, titled "OakDOT Geographic Equity Toolbox." Subtitle, "In Oakland, the City defines equity as fairness. It means that identity, such as race, ethnicity, gender, age, disability, sexual orientation or expression, has no detrimental effect on the distribution of resources, opportunities and outcomes for our City's residents. A sidebar reads, "The Priority Neighborhoods layer gives each census tract in Oakland a level of priority between lowest and highest determined by seven demographic factors: People of Color [25% of score], Low-Income Households (<50% Area Median Income) [25% of score], People with Disability [10% of score], Seniors 65 Years and Over [10% of score]. The map is heavily shaded purple in areas labeled as "Coliseum/Airport" and "Central East Oakland". There is light purple shading in "Eastlake/Fruitvale", "Downtown", and "West Oakland." The other areas, "North Oakland/Adams Point", "Glenview/Redwood Heights, "North Oakland Hills", and "East Oakland Hills", are mostly white, with small bits of purple in North Oakland and the East Oakland Hills.](https://bike-lab.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2024/04/updated_GET_2023_2023-07-11-204323_xkhw-1024x462.jpeg)

[However, the toolbox can also be used to equity-wash politically-motivated proposals, as it was for the now-failed TOWN project at Howard Terminal. Racial capital is capable of using all kinds of tools.]

The vision for the Community-Led Traffic Safety Pilot program is to provide communities with the ability to propose and implement quick-build projects on Oakland streets. In preparation for the Council resolution, OakDOT held two community engagement sessions, one downtown, and one at the 81st Avenue Library in Deep East Oakland, to hear what residents thought about the program.

The OakDOT report highlights the stark difference in reception at the two different sites. Downtown, people love the idea; at 81st Avenue, they were actively opposed.

81st Avenue is Scraper Bike Team territory, so I work and ride there often. Slow Streets was massively unpopular in Deep East Oakland; barriers were constantly removed or run over, and as far as I can tell no one was ever seen walking their dog or having their kids do chalk art in the street at Plymouth and 103rd. What worked in Rockridge to produce community space on residential streets like Shafter never came close to working on the other side of High Street.

The type of quick-build projects covered by the program are quite popular among urbanists, as Oakland resident and SJSU professor Gordon Douglas detailed in his book, “The Help-Yourself City“. Douglas found that DIY urbanism projects are predominantly led by white and affluent residents, probably reflecting a sense of entitlement to remake the city according to their own visions. The Community-Led Traffic Safety Pilot is an expression of the that white urbanist vision. To residents of Deep East Oakland, the idea feels like it’s coming from outside the community.

But that doesn’t mean people in Deep East are unconcerned about street safety. East Oakland residents will consider urbanist solutions to issues in their community, when the community is allowed to lead the process. From the community engagement report:

Instead of discussing the pilot, residents brought up other traffic safety concerns that they felt were more pressing; and would call for infrastructure modifications and/or traffic enforcement that are beyond the scope of this pilot. One resident commented that she would not enter the street to install traffic calming devices because she does not even feel it is safe to bicycle on the streets in her neighborhood…

AC Transit’s Tempo Bus Rapid Transit line (BRT) on International Boulevard was a major safety concern. Residents expressed frustration regarding the BRT itself and the timing of the planned quick-build project intended to prevent motorists from using the dedicated bus lane as a high-speed passing lane. Other streets mentioned as high priority for safety improvement included arterials such as 73rd Avenue and 98th Avenue. The sentiment that affecting real change in these areas requires concrete to be poured was expressed on multiple occasions.

During the original roll-out of Slow Streets, OakDOT staffers noticed that survey responses about the program were highly positive in North Oakland, and highly negative in East Oakland. Their observations led OakDOT to go do the community engagement it should have done before implementing Slow Streets; that effort led to the Essential Places program. Essential Places was similar to the Community-Led Traffic Safety Pilot, empowering local communities to work with OakDOT staff to get design support and materials for small-scale projects that were important to them.

In some cases, the Essential Places projects weren’t specifically transportation-related; for example, the placement of multi-lingual signage about where to get COVID testing. In others they were typical transportation quick-builds, such as flex-post bulb-outs at La Clinica in Fruitvale to make the street crossing safer. But I think the most important project was on Ney Avenue.

Ney Avenue’s Eastmont neighborhood was at the center of a spate of gun violence. Residents wanted some way to make their street feel safer, and asked OakDOT to install traffic diverters. Substantial barriers were installed, and they’re still there four years later.

This isn’t really a bike+ped project analogous to diverters in North Oakland or Berkeley; Ney is not typically a corridor for bikes or pedestrians because it’s hillier than the alternatives. And, the project may or may not have had a substantial impact on crime in the area; shootings are down but it’s hard to attribute that to any specific intervention. It’s still important, for the simple reason that the neighborhood asked for something, and the city listened and acted on it.

The mistrust expressed by the community at the 81st Avenue Branch Library session is well-earned. For decades, infrastructure projects have harmed that neighborhood, and even today, residents feel that their voices are minimized in discussions about changes to their streets. The vision of the Community-Led Traffic Safety Program is to give the community more agency in those processes, which would be wonderful. To be successful, the program will need to work through the community’s skepticism of city processes. City staffers will need to let the residents develop the vision, listen humbly and openly to people’s concerns, and follow up words with actions. If you do those things, you can begin the long process of rebuilding trust.