Oakland is working on updating its Bicycle Master Plan. Since the last update in 2007, a lot has changed in Oakland, but I think the two most important changes affecting this plan aren’t related to cyclists or even cycling infrastructure. What’s really different is that Oakland has consolidated various different agencies into a new Department of Transportation, and also created a new Department of Race and Equity.

I spoke with Ryan Russo, director of the DOT, at its two-year anniversary party, about why a consolidated DOT makes a difference. His response, which I appreciate, is that it puts planners in charge of transportation processes.

The way the city had been organized, street projects were led by the Department of Public Works, and Public Works tends to see everything as an engineering problem. Bringing in someone like Ryan, who has not only a planning background but an understanding of the equity issues involved in working in a diverse, multicultural city. (Ryan came from NYC).

At the same time, the creation of the Department of Race and Equity provides a focus on social justice issues, and someone to advocate for them in city processes. I have not met Darlene Flynn, the director, but I’ve heard reports that she is, let’s say, skeptical about the equity implications of bike advocacy. And I think skepticism is always good.

So, that’s background for the event, which was quite different than any other bike plan meeting I’ve been to. There were a few of the inevitable Streetmix charts, and maps with stickers and lines on them, but the real action was out in the breakout rooms. In fact, when I first arrived the main auditorium was almost empty because everyone was out talking about specific issues in small groups, and those groups were using discussion frameworks from the Department of Race and Equity.

And for the most part, the issues were more substantial than is typical in bike plan processes (and frankly, most city processes). In particular, one of the breakouts provoked discussion of how the bike plan should address racially-biased policing in Oakland.

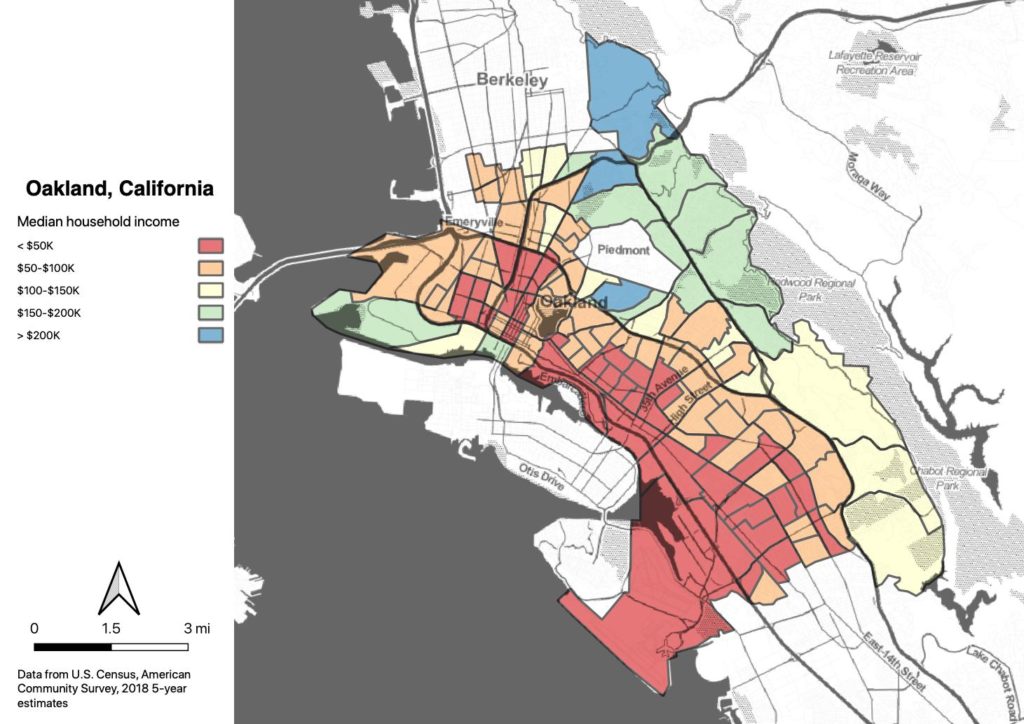

The posters noted that 60% of bicyclists stopped by Oakland police are Black. They also included statistics from the 2016 study on racialized policing which found that Blacks were far more likely to be stopped than Whites, and three times as likely to be searched and handcuffed, even though they are no more likely to be arrested or cited when stopped.

These are sobering statistics, and the conversations they prompt are deeper and more thoughtful than is typical in bike planning. And what’s fascinating about this process is that the DOT is putting these questions out in front, rather than tacking on an equity analysis at the end. It really creates the possibility that the new bike plan could become a tool for reducing social exclusions instead of reinforcing them.

Another way the process has increased inclusivity is by hiring local community groups to handle the outreach, instead of bringing in the usual suspects from large consulting firms. This event was run by the East Oakland Collective, a co-op of community activists working towards racial and economic equity.

I spoke to a number of city staffers at the event, and they had two shared thoughts. One, the process has been slower and messier than they’d anticipated. And two, that it has been really valuable, and it should be a model for other cities, and other planning processes in Oakland.

That’s an example of why Oakland is an awesome place to be studying the city. More so than almost anywhere in the country, it is grappling with every urban issue, and it has people who are part of the power structure who legitimately want to do the right things. And it has a history of activism which challenges hierarchical models.

You can’t solve hundreds of years of racial disparities with a bike plan. But you can try to avoid making them worse, and maybe even make a little bit of progress.