Last year I ran into the Oakland Rideout by accident. This year I’m a little more connected, so I heard about it ahead of time and went down to the Beastmode store to check it out.

Man, what a spectacular event.

Marshawn was there, along with RB, Naj, Nakari, and a bunch of other folks from Rich City and the Scraper Bike Team, but no one provided explicit leadership to the mass of hundreds of riders (I’m guessing 800+). We started by taking over an intersection in Old Oakland with music and stunt riding for about an hour. OPD had pretty clearly decided not to hassle the group; we were just one block from the city jail, so there were plenty of cops around, but there was thankfully no police presence at 8th and Washington.

The group headed out to West Oakland, and went up San Pablo, Adeline and Telegraph to the Berkeley campus, where we rode over the “NO BIKE RIDING” signs onto Sproul Plaza, which probably hasn’t seen that many black people since MLK spoke there in 1967.

The thing I find fascinating about the event is its joyful reclamation of urban space. The Rideout uses the radical tactics that Critical Mass pioneered (and Bike Party has mostly eschewed), but the social underpinnings of the ride are very different. Critical Mass, maybe not when it started in 1992 but certainly by its peak in 1997, was fundamentally a movement about entitlement. It marked a shift in the value systems of an affluent sub-culture, which rejected the surburban car culture of the elder generation and saw the bicycle as a tool to create a new urban lifestyle. (Similar dynamics exist today in the YIMBY movement.) The battles over Critical Mass were battles of entitled cyclists against entitled drivers, and once San Francisco decided to entitle the cyclists by adopting its first bike plan, the ride lost its momentum.

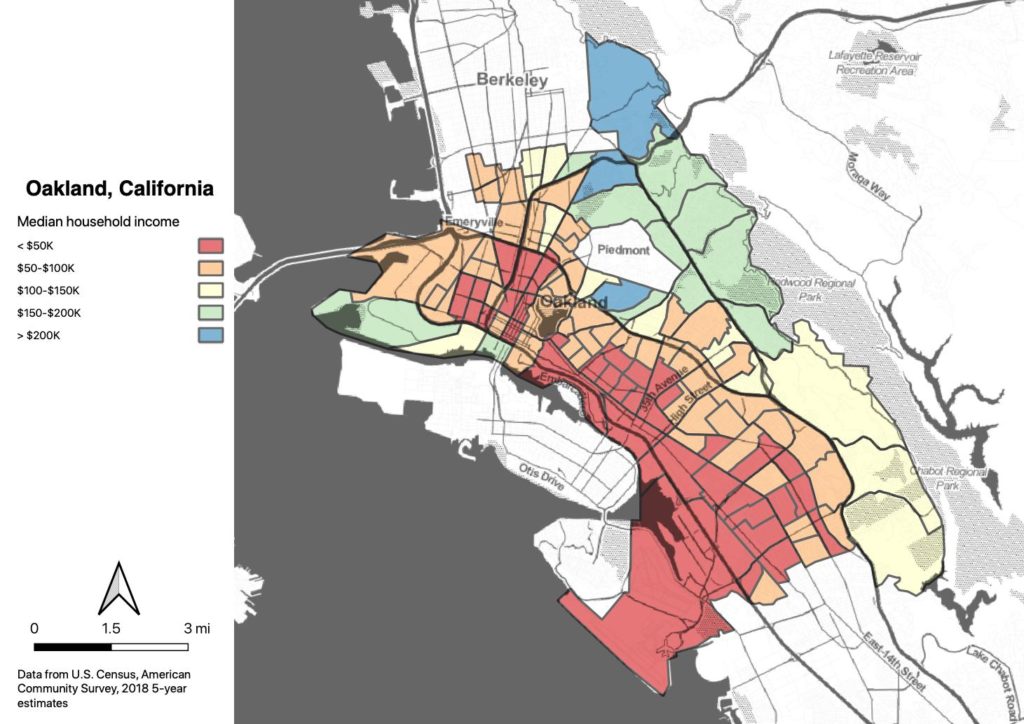

The Rideout is different because it’s grounded in disadvantage. In the same way as sideshow culture, the Rideout claims urban space for groups which are usually marginalized, persecuted or erased in urban space.

They are claiming the right to the city.

The ride prompted me to re-read some Lefebvre, and man, that guy could think. So I’m about to get dragged down a rabbit hole investigating the relationships of spatial production, economic production, radicalism and the exercise of state power. But here I’ll just drop a couple of quotes:

Space is not a scientific object removed from ideology or politics. It has always been political and strategic. There is an ideology of space. Because space, which seems homogeneous…is a social product.

Lefebvre is challenging the idea that a place like Sproul Plaza is created by its architects or designers, or by the authorities who own it or manage it. Space is created by its social usage, and spatial radicalism can challenge the power structures which underly the way the space is produced. Sproul Plaza itself has been the location of a number of such challenges, some successful.

David Harvey writes about Lefebvre’s the Right to the City:

The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources: it is a right to change ourselves by changing the city…[T]his transformation inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanization. The freedom to make and remake our cities and ourselves is…one of the most precious yet most neglected of our human rights.

I don’t know if Marshawn knows anything about urban critical theory. But as someone who grew up in the Oakland projects, he knows about sideshows, and sideshows are a spectacular example of a group exercising collective power to reshape spatial practice.

During the ride, one annoyed driver (white dude, of course) leaned his head out and asked me what the event was. I told him, “Oakland Rideout!” He then asked “what’s it for?” (“Fun!”) and “can’t you do it some other way?”

I was at the Cal football game when Marshawn grabbed a trainer’s golf cart and drove it around the field after a spectacular overtime finish. (Name drop: I was with Desmond Bishop’s cousin, and Desmond had just intercepted a pass to seal the victory.)

And the answer is, no, Marshawn can’t do it some other way. He has to be Marshawn. Rich City Rides and the Scraper Bike Team have to do it their way, too. They have to do what’s real for themselves and their communities, and assert their right to the city in the ways that make sense to them.

My challenge to traditional bike advocacy is to find a way to embrace and lift up this movement, the way it embraced Critical Mass. The Rideout started just a few blocks from the Bike East Bay HQ and I didn’t see any representation from them. (It’s possible I missed it; the ride was huge). This is literally the biggest bike event in Oakland. We’re always talking about wanting to get more people of color involved in cycling; the Rideout is proof that they’re already involved. We just need to meet them where they are instead of expecting them to ride like they’re from Copenhagen.

Thanks, Marshawn!