I read a ton of articles and project proposals, and I keep encountering a trope about disproportionality. Generally it’s mentioned in the introduction or conclusion that poor people of color are disproportionately impacted by the societal harms related to the topic the author is writing on. Whether it be pollution, housing insecurity, food insecurity, or health issues like asthma, diabetes, and now COVID-19, low-income BIPOC have it worse than anyone else. The trope goes further, to employ the fact of disproportionate disadvantage as a justification for the author’s favored project: a bike lane, or a housing development, or a park or an urban farm or whatever it is the writer thinks is important.

I will note that it’s generally true. BIPOC have been disadvantaged in America since Columbus first showed up, and the effects are still seen throughout our society. Systematic, structural racism remains prevalent in the U.S., with impacts on every aspect of BIPOC’s lives; wealth, health, education, employment, policing, etc.

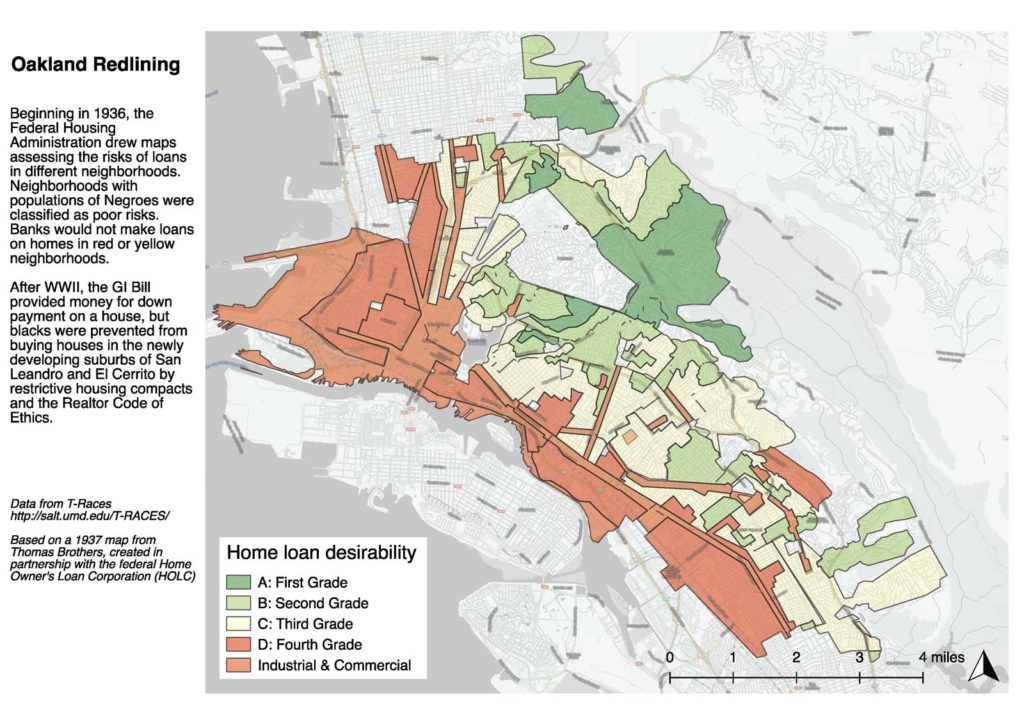

Here are some examples from Oakland., starting with the redlining map from 1937, which disadvantaged people of color, especially Black people, preventing them from obtaining housing loans, and spurring disinvestment in their neighborhoods.

Redlining was not just a broad characterization; FHA’s evaluation was based on a detailed analysis of how many non-white people lived in a neighborhood. You can see the commentary connected to the maps at the Mapping Inequality project web site. I was wondering why there was a bit of red surrounded by yellow in North Oakland, in the Bushrod neighborhood, and here’s what the Federal Housing Administration had to say about why that spot is redlined:

Clarifying remarks: Unless one knows about the colored families living in the district, there is no means of distinguishing their homes from those of their white neighbors. The homes of the Negroes are in many instances better kept than the adjoining homes of white owners. Loans in this area should be governed according to hazard.

In other words: There were Black middle-class people living in Bushrod (FHA estimates about 12 families). Even though they were working, presumably making good money, and keeping their property up well, it was still “hazardous” for FHA to issue loans there, because the presence of Negroes implied the future presence of more Negroes, which was assumed to lead to degradation and decay. This racist policy, especially after WWII, resulted in huge wealth disparities between white people who could get home loans and Black people who could not.

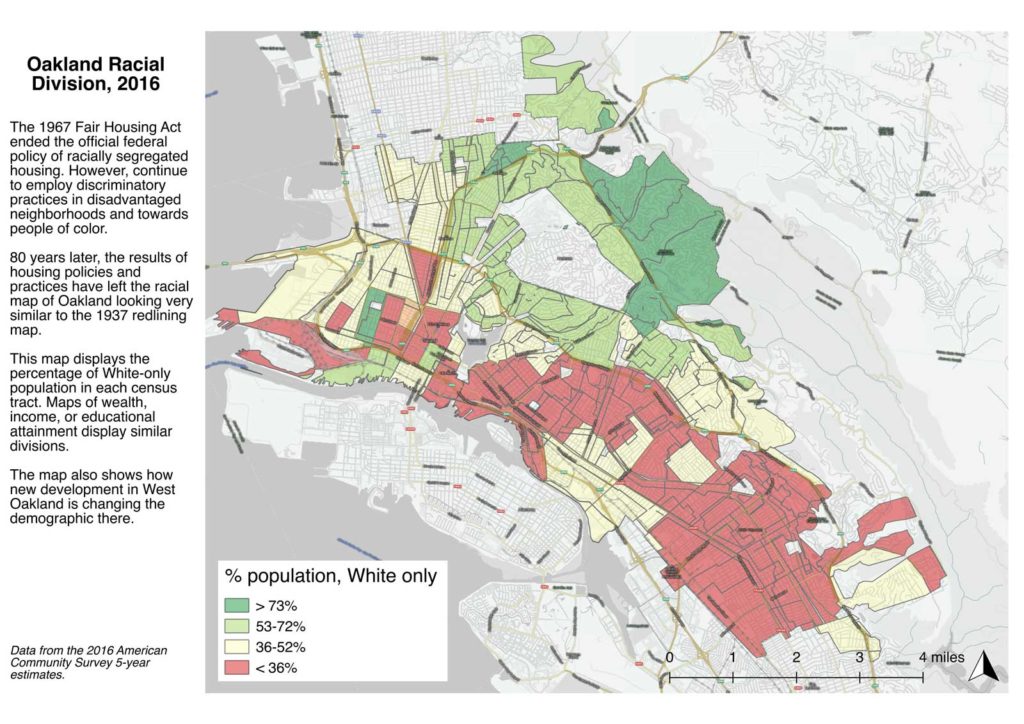

America followed that up by investing in the white suburbs and disinvesting in the non-white central city, with effects still visible today. Here is Oakland’s current racial makeup, which still has strong echoes of the above 1937 redlining map.

And because we live in a society of profound inequality and structural racism, the geography of every societal ill still aligns with this 80-year-old map.

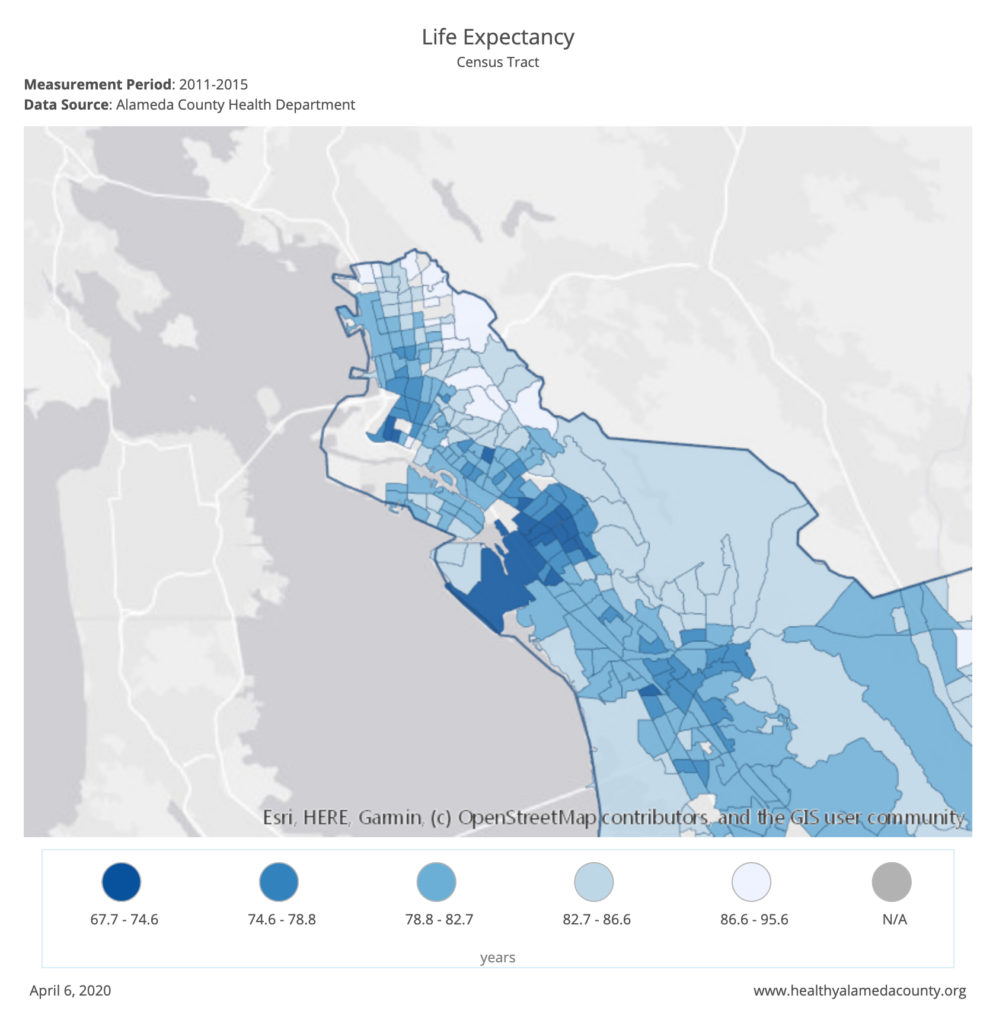

Here’s life expectancy (source: Alameda County Health Department). The difference in life expectancy at birth between the West and East Oakland flatlands and the hills is as large as 15 years.

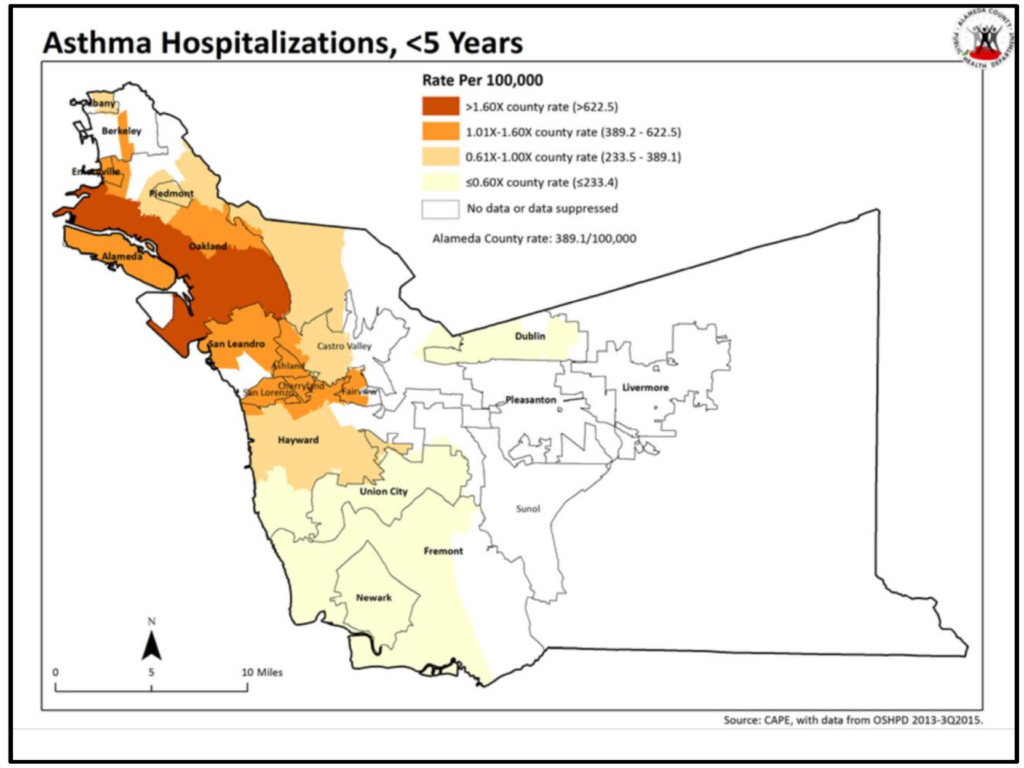

Here are asthma-related hospitalizations of young children, by neighborhood (source: Alameda County Department of Public Health). West and East Oakland are the worst; the northern hills aren’t even colored (<10 cases).

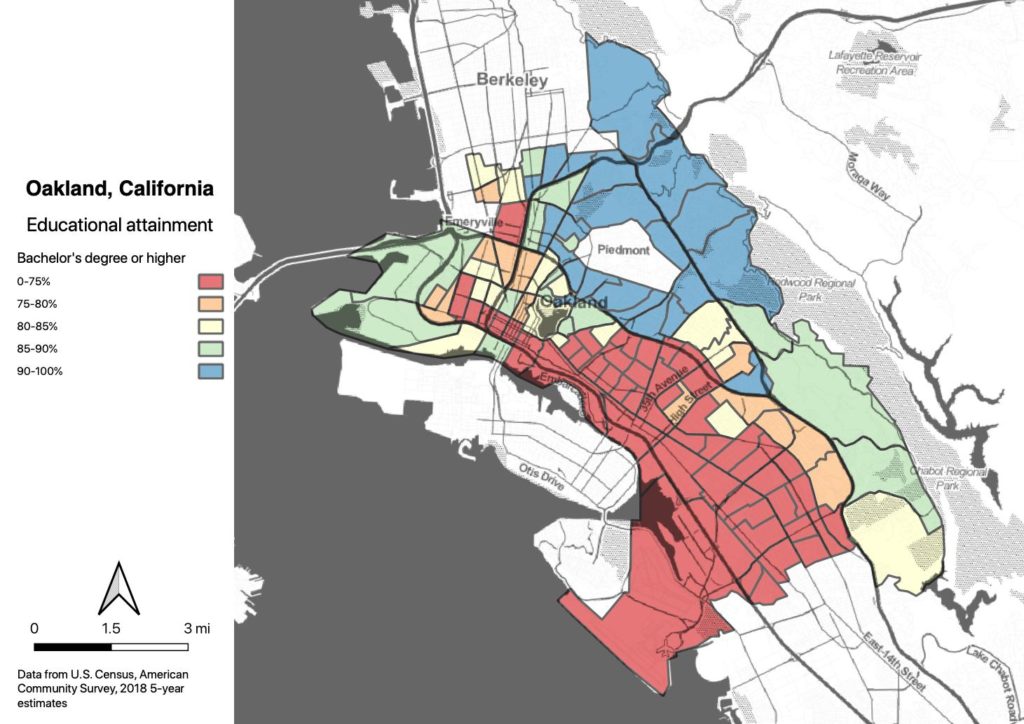

Education follows the same geography; here’s educational attainment, bachelor’s degree or higher, for Oakland residents. In some of the census tracts in the hills it’s as high as 96%; in East Oakland some tracts are below 50%. West Oakland would have been red 20 years ago; higher levels of educational attainment are seen there now due to gentrification, not due to increased education of existing residents.

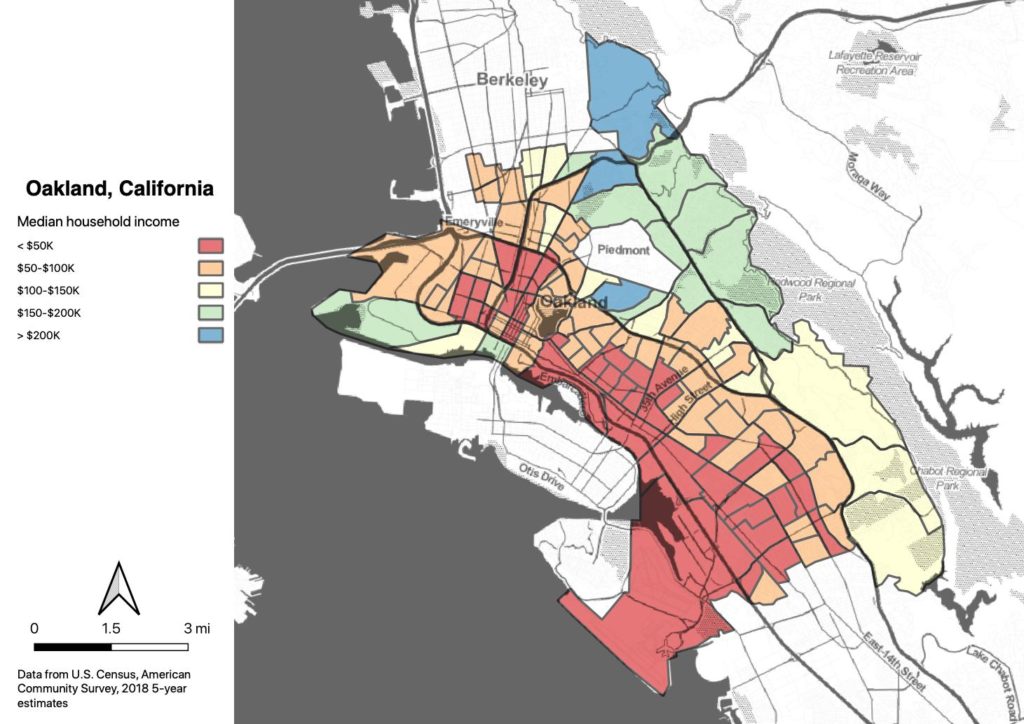

And of course, educational attainment maps to household income, which is above $200K (median!) in the hills to the north, and below $50K in almost half of the city.

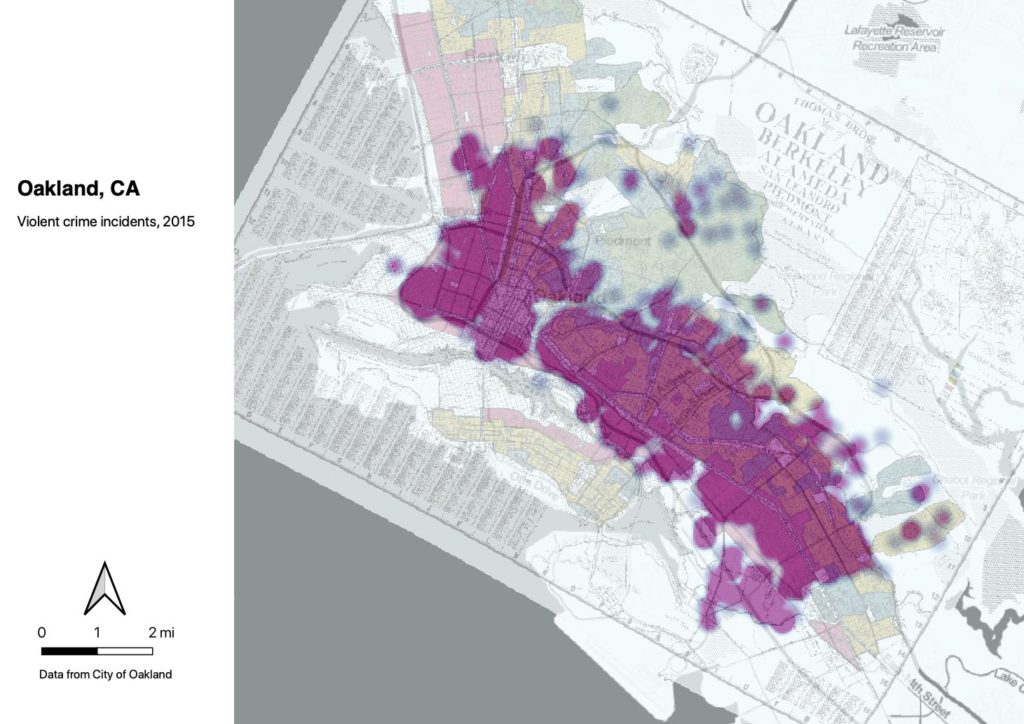

How about crime? Here are violent crime locations in Oakland for 2015 (last year I found a full data set), overlain on the redlining map. Virtually all of the violent crime is west of 580, which was constructed in the 1960s to separate the hills from the flatlands, following the division of the redlining map.

And finally, The Bike Lab’s work on policing of bikes and pedestrians in Oakland showed that disparities in discretionary stops follow the same geographic and racial lines.

None of this should be surprising; numerous authors and researchers have been pointing out these spatialized, racialized disparities, and the resistance to the concept is less entrenched than it used to be, thanks to the work of folks like Ta-Nehisi Coates (The Case for Reparations), George Lipsitz (How Racism Takes Place), Richard Rothstein (The Color of Law) and others.

Disadvantage in the age of COVID-19

Now we’re at a moment where society is facing massive upheavals, and there are already indications that the pandemic will disproportionately disadvantage BIPOC in America. Black and brown people appear to be substantially more likely to die from COVID-19, probably because of a combination of greater exposure to the virus, lesser access to health care, and substantially higher underlying health risks. Once we have more data, we are likely to discover that BIPOC are more likely to have lost their jobs, more likely to have lost their housing, more likely to have had interruptions in their education, and so on. All of it is sadly predictable, because that’s the way the system works.

Here’s where the trope of “disproportionate impact” runs into trouble. Disadvantaged communities are disproportionately impacted by all our societal harms. (That’s why we call them disadvantaged.) So the fact of disadvantage cannot be used as justification for a particular intervention, unless that intervention is specifically rooted in addressing the history of societal harms experienced by that community.

Here’s an example from Oakland. This week, with great fanfare, the city rolled out a plan to “close” 74 miles of streets to cars. I found the press conference…interesting. Libby Schaaf, introducing the concept, framed the program as focused on recreational walking and cycling. She said, “Oakland Slow Streets is trying to send a message that we want Oaklanders to recreate in a socially distant manner.” Ryan Russo (OakDOT) followed, and his framing is that the program implements part of the bike plan. “What we’re doing is publicizing a set of streets we’ve already studied.” Desmond Jeffries, speaking on behalf Councilmember Rebecca Kaplan (who generally opposes Schaaf), claims that it’s a transportation program. “”This is not a space for recreation…this is for people to be safe as they’re going to grocery stores and going to work.” Councilmember Noel Gallo used his time to talk about using policing to stop sideshows, and to complain that Fruitvale’s streets have potholes.

The program can’t be all of these things at the same time. What’s really going on?

The same day, coincidentally, The Untokening published their white paper on Mobility Justice and COVID-19, which came out of a webinar I joined a couple of weeks ago. Led by Adonia Lugo and Monique G. López (Pueblo Planning), it convened mobility justice advocates to share concerns about responses to the COVID-19 crisis.

On the call, Lynda Lopez (@23:30) raised some issues about the push for street closures in response to the need for social distancing.

It concerns me if you have no way to prevent people from congregating, how is that going to be a good issue for public health?…Some people are using this moment to advance transportation ideas that…it just doesn’t seem to be the place for it right now.

…We’re not talking about how marginalized communities are staying safe, that’s not the center of the conversation. Instead it’s like, how do we keep these trails open so I can go jogging? It feels like a misplaced priority. Center who needs to be centered right now; people are literally dying.

Monique López (@25:30) responded that “some folks are using this moment to advance ideas that they’ve already had…not keeping at mind and at the heart of what they are doing, the impacts on vulnerable communities.”

Lugo (@28:30) in her characteristically incisive way, described the conversation about open streets as “opportunistic, to focus on expanding a recreational network…how are we ensuring that people are able to access their basic needs? Who is being centered is really key here…who is moving by choice, and who has the privilege to not be moving by choice?”

That term, opportunistic, really struck a chord for me. People are arguing that the age of COVID-19 is the perfect time to advance whatever their pet project is. The crisis is proof that we need open streets, or more apartment buildings, or that we need to reinvest in the suburbs, or that we need free transit, or more private vehicles, or wider sidewalks or protected bike lanes.

None of that has any real relevance as a response to the reality of a global pandemic.

The street closure program was advocated for and implemented by people who’ve been talking about increasing street closures for years. That they chose this moment to act is opportunistic, and an expression of who holds power in the city.

The Untokening white paper has a great set of mobility justice principles; here are a few which are relevant to Oakland Slow Streets and bike/ped planning in general:

- Do not plan future projects at a time when equitable public participation is impossible.

The Oakland Bike Plan did a good job of equitable public engagement, and the “74 mile” figure Oakland is using comes from streets identified in the bike plan as “neighborhood bike boulevards.” But the bike plan doesn’t specify how those streets will be changed. It certainly doesn’t specify that they will be closed to through traffic. And while this program is specified as an emergency measure, it seems likely that Schaaf and Russo will use it as a prototype for more permanent street diverters, the sort of tactical urbanism that Russo championed in NYC. The communities haven’t really been consulted. If this is an emergency measure, when the city later wants to make the diverters permanent it will have to do better than token engagement. - Redirect mobility planning staff to meet essential needs for vulnerable communities.

Oakland Slow Streets will be implemented in a way that’s not particularly labor-intensive, but managing the program, and putting out and maintaining signage on 74 miles of streets will take staff time. And with few exceptions, the proposed interventions are not meaningful improvements to the transportation network for bikes and pedestrians. So despite Jeffries/Kaplan’s comments, Slow Streets is not about moving people around the city.

Members of disadvantaged communities who are still employed are disproportionally employed in working-class jobs which have now been deemed to be essential. They’re the ones driving the buses, staffing the grocery stores, running the take-out joints and doing food delivery. They do not have the privilege to not move; they are compelled to be out there, exposed to the pandemic. How is OakDOT helping them get around the city with transit services significantly curtailed? - Define street safety in a way that centers the most oppressed and vulnerable groups. Policing is not a tool for healing our divided communities, and official street closures usually involve police. These are not a solution for equitable street safety in communities of color.

Schaaf asserted that Oakland will not be issuing citations for violations of the Slow Streets closures. But the City of Oakland has a decades-long history of being unable to control OPD, and in particular, being unable to stop OPD from persecuting Black people. Discretionary traffic stops in West and East Oakland are predominantly pretexts for shakedowns; providing another pretext could exacerbate the problem. And Gallo is explicitly calling for more policing. - Direct public funding to community bicycle shops that can distribute vehicles and provide repair at a neighborhood level.

Here’s something Oakland really could be doing. I was up visiting Rich City Rides last week, and the shop was super-busy, with what looked like a mix of survival cyclists trying to fix up the bikes they need to get around, and families pulling their kids’ bikes out of storage and trying to get them on the road. There’s clearly demand.

We have community shops like Cycles of Change who are set up to distribute bikes. They could be easily funded to provide that service. Oakland also has a ton of impounded bikes in storage; we could give those out to people who need them.

How would adopting mobility justice thinking affect Oakland’s response to the crisis?

Back to proportionality

The problem with disproportionate impact—besides its existence and its effects on BIPOC—is that its very ubiquity limits its usefulness as a tool for policy analysis. If BIPOC communities are disproportionately impacted by everything, the fact of that impact can be used to justify practically anything.

In discussing Oakland Slow Streets with advocates, the concept that the change is justified by disproportionate impact has crept back in. Two examples from Twitterers arguing on behalf of the program:

We’ve been privileging automobiles for 100 years primarily to the advantage of wealthy, white people, with a goal of segregation and social isolation, enforced by a massive police regime to ensure pedestrians comply and are criminalized if they don’t. Reversing that is good.

love seeing woke planners complain about the “cultural erasure” of prohibiting cars on streets where black, Asian, and latinx children have been killed riding their bikes.

It is true that, in Oakland, BIPOC pedestrians and cyclists are more likely to be hit by a car than white pedestrians and cyclists. But that fact cannot become a blanket justification for every possible intervention to protect pedestrians and cyclists. Because BIPOC pedestrians and cyclists are also more likely to be impacted by every other social ill which plagues Oakland, and many possible bike/ped interventions can make those other social ills worse.

For example, as noted above, West Oakland is the worst place in the East Bay for childhood asthma. Traditional bike advocacy argues that therefore, we should install more bike infrastructure in West Oakland, to increase physical activity levels and give people transportation options which might reduce driving. But the reason childhood asthma is high in West Oakland is primarily because of high levels of particulate pollution from the port and the freeways. Bike infrastructure isn’t going to fix those problems, and if kids are regularly riding around in air with high levels of particulate pollution, it could make asthma worse.

And as I’ve noted before, the pairing of bike infrastructure with economic development in order to build political capital has led to bike infrastructure becoming associated with displacement and gentrification, with impacts primarily borne by low-income BIPOC.

American bike advocacy has articulated a specific goal: advocates want a connected network of low-stress bikeways, like those found in Amsterdam and Copenhagen. Those advocates are generally willing to assume that this goal is morally neutral and not connected to societal systems of oppression. (Except, perhaps, the oppression of non-drivers by drivers). But when you have already chosen your goal, and then you advocate for it by claiming it will address societal systems of oppression, you’re not elevating the struggle of oppressed people. You’re appropriating it.

If you really want to address oppression, you have to begin with the lived experience of oppressed peoples, and give them agency in finding solutions. What do parents in West Oakland know about the sources of pollution in their neighborhoods? How important is the problem to them? What would they like to see change? I don’t know the answers, but if you’re claiming to address the disproportionate impact of childhood asthma, you must ask those questions before you suggest a solution. And you must be willing to accept that the visions of the people affected may differ from yours.

In our current American moment, low-income BIPOC are being disproportionately slaughtered by a global pandemic. They are also at disproportionate risk of long-term financial hardship due to the economic shutdown. Both the disease and the response to it will disproportionately impact those communities. (Because, again, that’s the way oppressive systems work).

Is shutting down streets so that people can jog and walk their dogs a proportionate response?

Conclusion

“Freedom is foundationally about having the ability to make choices in our lives. Freedom of movement in the current context means having the choice not to move at all.” –Untokening, Mobility Justice and COVID-19

I was today years old when I found out that EBT cards can’t be used to buy groceries online. My white, professional-class family never had to interact with America’s social welfare systems, or to experience the ways that they contribute to oppression. In the age of COVID-19, they’re contributing by reducing access to healthy food and increasing exposure to risk of infection among already-vulnerable populations. And while I get to sit home and write grant proposals and blog posts, working-class people are out there getting exposed.

I love riding bikes (and unicycles). I’ve been able to ride almost every day, and there’s no question that it’s good for my mental health. It would be really hard on me if the U.S. were to decide to restrict outdoor recreation, as Spain and Italy have. But I have to contextualize that as part of the crisis we’re in. My frustration at not being able to ride or walk the way I might want to is nothing compared to having to deal with housing insecurity, food insecurity, and the threat of serious illness and death. If I have to stay shut in for a few weeks, I can deal with it.

So, I’m not saying that Oakland shouldn’t close streets to cars, but I am saying that it doesn’t feel like a proportionate response. It centers the needs of people like me who have the freedom to stay at home and want to make the choice to go outside for recreation, instead of centering the needs of the most vulnerable. It’s not the only thing the city has done in response to the crisis, but it is the only one which has involved an in-person press conference, and it’s the only one which other cities are being pushed to emulate. That says a lot about who city leaders are trying to speak to (and, who city leaders are listening to).

My challenge to advocates who want to address disproportionate impacts—no matter what you are advocating for—is to flip your script. Don’t start with a proposal; start by talking to the impacted groups. Try to understand their experiences and their priorities. Listen to what they have to say, learn about how they’re already coping, and see if you can figure out how your idea fits into their framework. If you do it the other way around, you’re contributing to their marginalization.